A walk through Picasso's 'Landscapes'

This article was published in The Charlotte Ledger e-newsletter on February 18, 2023. Find out more and sign up for free here.

A critic’s guide: The Mint’s ‘Picasso Landscapes’ exhibit brings together sides of the artist that are not often seen in one place

by Lawrence Toppman

Quick: Name any Picasso masterpiece that comes to mind.

“Guernica,” surely. “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” probably. Maybe “The Old Guitarist,” “The Weeping Woman” or “Three Musicians.” Perhaps his sketch of Don Quixote or portraits of Gertrude Stein, Dora Maar or his own somber self.

How many of these are landscapes? Zero. So when you learn the uptown Mint Museum has opened a show titled “Picasso Landscapes: Out of Bounds,” you might think, “Minor stuff. I could skip it.”

If so, you’d be wrong.

You likely won’t see anything familiar in this grouping of more than 40 works, the first traveling exhibit to explore his lesser-known affinity for landscapes. But you’ll see how he progressed from an astonishing teenager blending realism and impressionism to an older man who figuratively opened his head and let every thought, dream and vision fly out.

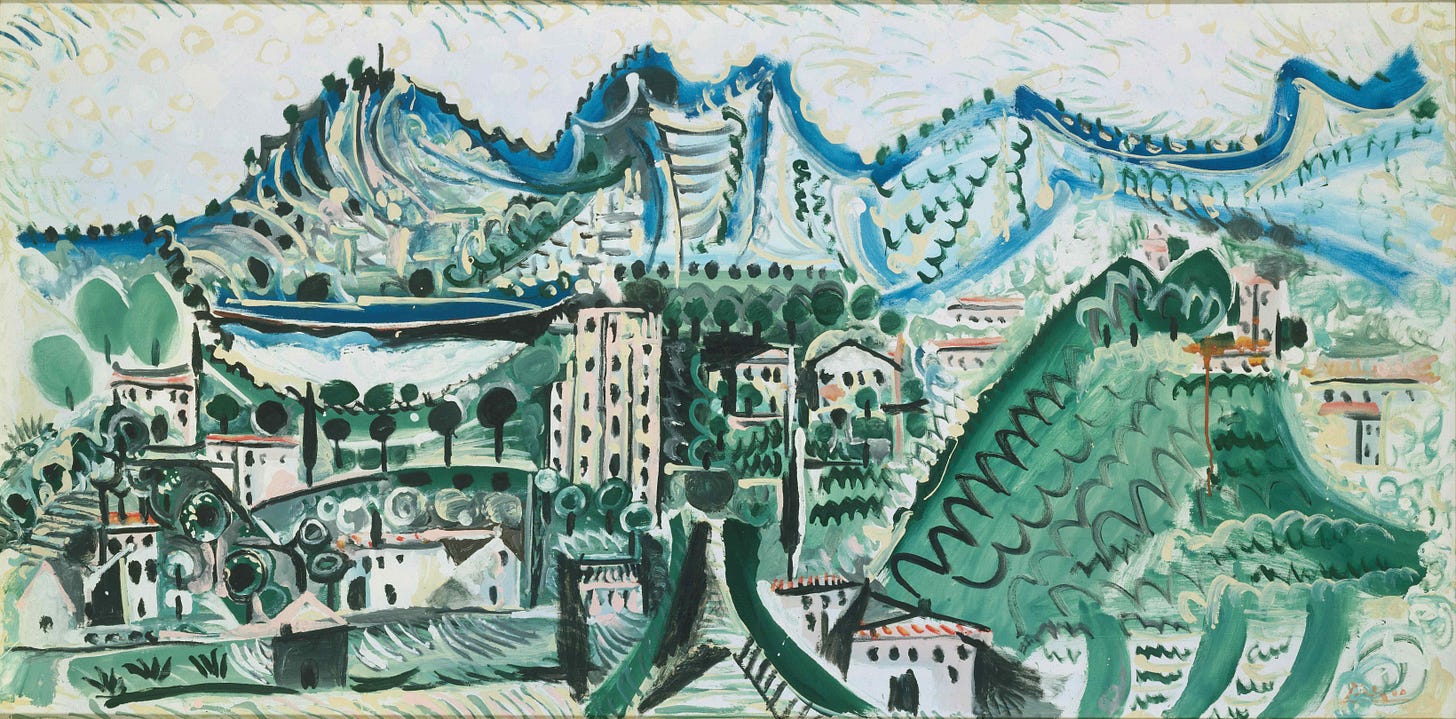

The exhibit smacks you on the nose as you step into it. “Landscape at Mougins II,” painted in 1965 eight years before he died there at 91, shows greenery run amok. Great verdant swaths obscure buildings and spread through the streets and rise up at the back like some kind of tsunami about to drown the town.

Yet step around the corner to the beginning of this mostly chronological exhibit, and you encounter the delicate “Mountains of Málaga” and subtle “Grove,” executed before he reached 20 with amazing skill for one so young. (People forget that Picasso, a great draftsman, could be faithful to life when he chose.)

You see the artist’s likeness throughout the exhibit in photos and silent films: wary, pugnacious, smiling on rare occasions like a wrestler figuring out how to take you down. He appears in only two paintings, both from later years when he embarrassingly asserted his aging virility. In “L’Aubade: The Serenade,” the naked Picasso plays an enormous clarinet shaped like a penis, while a nude model leans back, eyes closed, with a satisfied smile. Ummmm … no thanks.

One of the first-rate wall panels likens this to Titian’s “Sleeping Venus,” and you can see Picasso measuring himself against predecessors all through this show. He bellies up to Van Gogh with an evening in Provence, where the latter painted “Starry Night”; to Pissarro in a Parisian city scene with splashes of color; to Cezanne in views that conceive of nature in geometric ways.

He often does this with humor or even mockery. In Manet’s “The Old Musician,” five people surround a violinist sitting in melancholy silence and wonder what to make of him. In Picasso’s “Guitar Player and People in a Landscape,” the musician strums avidly for five hearers who barely care and resemble, among other things, a peacock, a goat and a spider monkey.

Cubism, which Picasso helped invent, naturally figures in some of the earlier works. The 1909 “Landscape with Bridge” reduces man-made structures to triangles, squares and half-circles, yet nature — represented by a round green leaf and a surging river — can’t be treated the same way: It’s wild, irreducible to simple shapes. Mountains in later paintings, triangular though they be, don’t seem abstract.

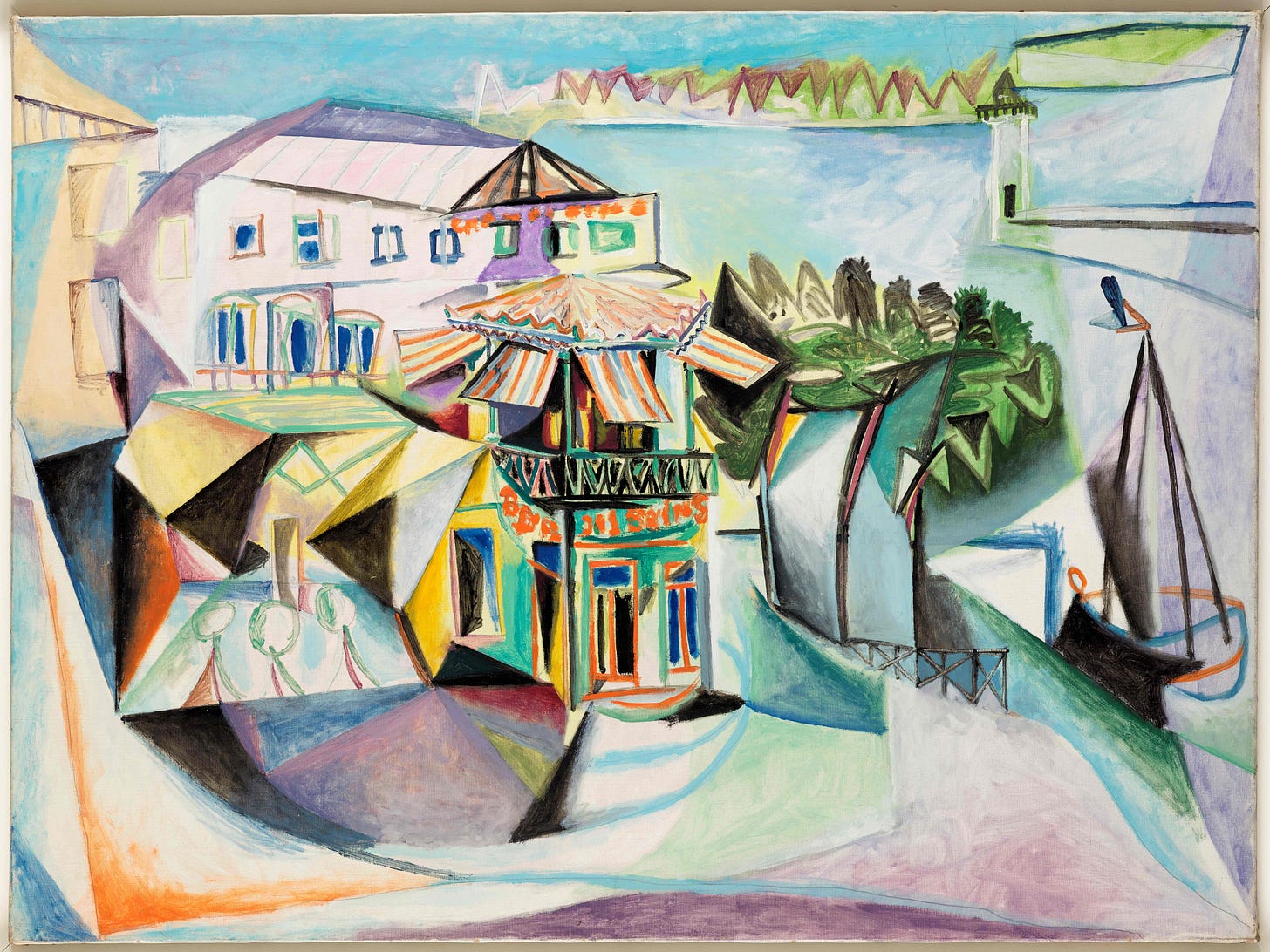

Picasso’s landscapes almost never have people or even animals in them. The title structure in the 1940 “Café en Royan” beckons invitingly, with gaudy striped awnings and brightly framed windows, in the center of town. Yet there’s not a soul around; the square remains as disturbingly empty as a cityscape by De Chirico.

Picasso rarely made direct references to current events, “Guernica” aside, but maybe he was showing his feelings for a France occupied by Nazis; Paris fell in the spring of 1940. I suppose he preferred nature to humanity in any case: “View of Cannes at Dusk” initially seems idyllic, with a tangle of foliage and two birds, but reveals a construction crane gnawing at the Cote d’Azur.

He was equally adept with riots of color, as in the popping red, blue, yellow and orange of the cheerful “Landscape of Juan-les-Pins,” and a limited palette. He used only tones of brown, gray and white to depict a Parisian park in “Snow Landscape.” Bare trees twist naturally in front of a misty, impressionistic background of flakes and mysterious foliage, an image that draws you in.

The exhibit concludes with a space full of collages and paintings by Charlotte-born Romare Bearden. I didn’t need an excuse to revisit such old friends as “Carolina Shout” and “The Train,” but the curators believe these men were linked by interests: bulls and bullfighting (definitely), use of windows to juxtapose exterior and interior action (yes, though that’s common), music (vaguely) and religion (maybe, but not clearly in this show).

Bearden’s early sacred paintings, especially “The Annunciation” and “Madonna and Child,” will knock you over. Visualize richly hued stained-glass windows rendering humans as cubist near-abstractions, and you’ll have the idea. Many artists working between 1900 and 1960 owed some kind of debt to Picasso, and Bearden pays it beautifully here.

Lawrence Toppman covered the arts for 40 years at The Charlotte Observer before retiring in 2020.

Need to sign up for this e-newsletter? We offer a free version, as well as paid memberships for full access to all 4 of our local newsletters:

Subscribed

➡️ Opt in or out of different newsletters on your “My Account” page.

➡️ Learn more about The Charlotte Ledger

The Charlotte Ledger is a locally owned media company that delivers smart and essential news through e-newsletters and on a website. We strive for fairness and accuracy and will correct all known errors. The content reflects the independent editorial judgment of The Charlotte Ledger. Any advertising, paid marketing, or sponsored content will be clearly labeled.

Like what we are doing? Feel free to forward this along and to tell a friend.

Social media: On Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn.

Sponsorship information/customer service: email support@cltledger.com.

Executive editor: Tony Mecia; Managing editor: Cristina Bolling; Staff writer: Lindsey Banks; Business manager: Brie Chrisman, BC Creative