Inside Charlotte’s private cadaver lab

On a recent evening, we joined a 15-person class that offers an up-close look at the human body

The following article appeared in the April 8, 2024, edition of The Charlotte Ledger, an e-newsletter with smart and original local news for Charlotte. We offer free and paid subscription plans. More info here.

Near Charlotte’s airport, Experience Anatomy opens hands-on human dissections to local massage therapists, yoga teachers and others; a destination for medical training

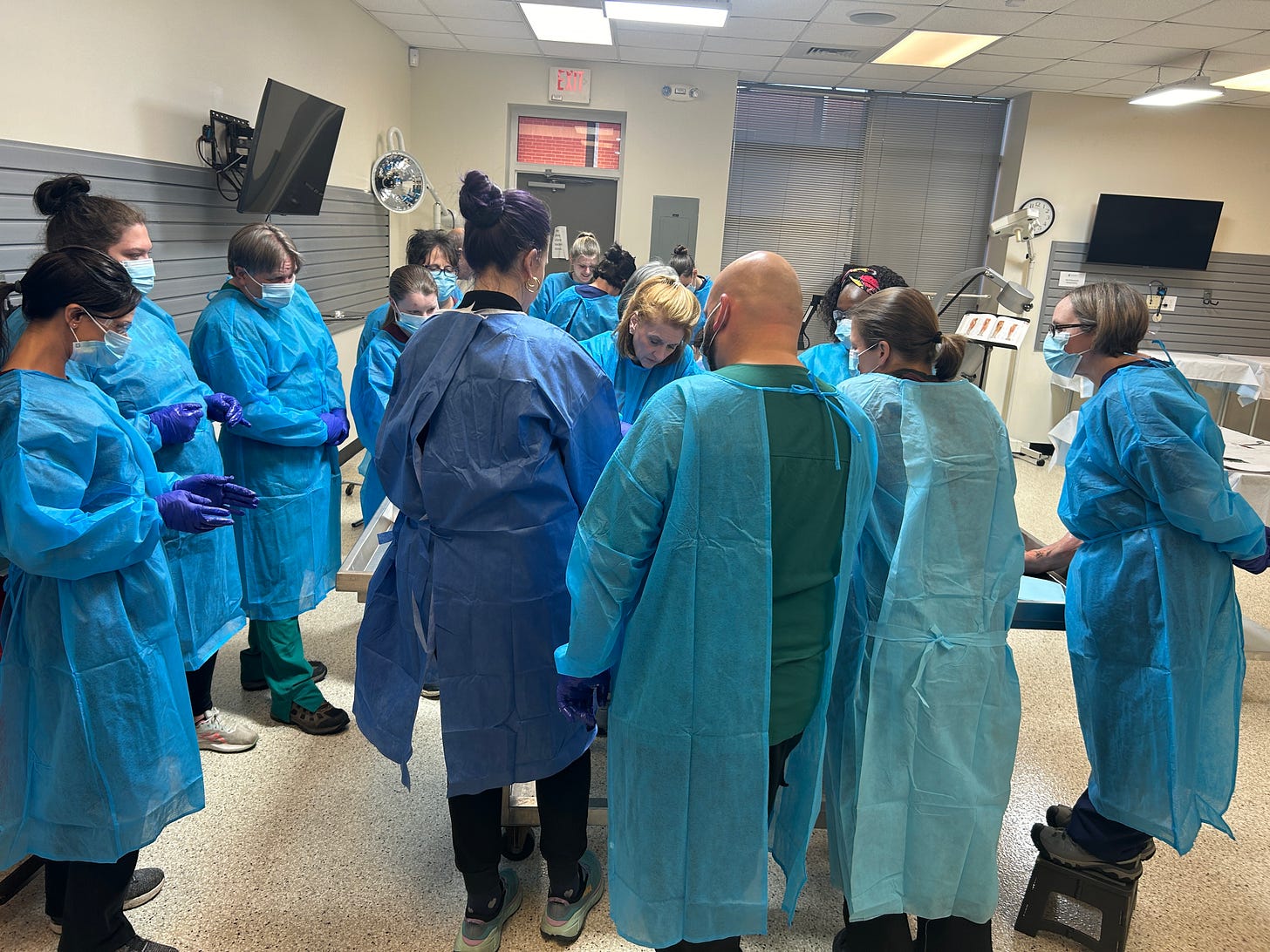

Typically, cadaver labs are places for medical students. But at Experience Anatomy, customers ranging from yoga instructors to nurses pay $175 for a 4-hour session to explore the human body. (Photos by Michelle Crouch)

by Michelle Crouch

Co-published with N.C. Health News

In a nondescript office building near the Charlotte airport last month, adults in blue gowns crowded around the body of a woman who had died of cardiovascular disease. An instructor gently pressed her gloved finger against the woman’s lung and invited the others to do the same.

“If you’ve never felt a lung, you need to feel a lung,” she said. “Most people think lungs are like a balloon, but they are more like a kitchen sponge. They have millions of tiny air sacs.”

Later, the class felt the stones in the cadaver’s gall bladder and took turns holding her heart in their hands.

“Wow, that’s amazing,” one woman whispered when she was handed the heart. Another person compared the organ’s texture to the velvety skin of a stingray.

None of the people in the lab were doctors or medical students. They were participants in the Dissection Club at Experience Anatomy, a private cadaver lab that offers nurses, yoga teachers, massage therapists and others deeply interested in anatomy an opportunity to dissect the human body.

In the past, cadaver dissections were mostly reserved for doctors and medical students. But Jamie Decker, founder and CEO of Experience Anatomy, believes the experience should be accessible to everyone, especially students and professionals who work on living people’s bodies.

“I’ve seen so many people have an ‘aha’ moment in the cadaver lab, young and old alike. Why not allow more people to have that experience?” Decker said.

An unusual Christmas gift

There are other cadaver labs in Charlotte and across the state, including one at Atrium Health Mercy. Most are part of medical schools or physician residency programs and are used only for medical students and healthcare industry training programs.

On the night a Ledger/NC Health News reporter visited Experience Anatomy, the 15-person class included a yoga teacher, a physical therapist, a nurse, a reflexologist, an acupuncturist and seven massage therapists. They said dissection gives them a deeper understanding of the body so they can better serve their patients or clients.

“It helps me understand what I’m seeing and feeling when I work on patients,” said Katie Hopkins, 33, a repeat participant who is a massage therapist, movement educator and owner of Align & Spiral in Charlotte.

Also participating was Providence Day School student Emma Adams, 18, who plans to go into forensic pathology, and Judy Hannon, a 49-year-old museum conservator from Maryland. Hannon said she asked for the experience as a Christmas gift.

Emma Adams, a senior at Providence Day School in Charlotte, has attended more than a dozen dissections at Experience Anatomy.

“If I had a more scientific mind, I would have done mortuary science or forensic pathology,” said Hannon, whose background is in art. “I think it’s absolutely fascinating. I was blown away by each layer we removed.”

Inspired by Body Worlds exhibit

Decker said her interest in tissue preservation was sparked in high school when she visited the Body Worlds exhibit that visited Discovery Place Science in 2007. The traveling exhibit uses real human bodies that have been preserved using a technique known as plastination.

Decker went on to get a degree in mortuary science. From 2012 to 2014, she ran the gross anatomy lab at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk. There, she often worked with health care companies who rented the lab (and its cadavers) on evenings and weekends for training physicians on new techniques and implants, she said.

“It opened up my mind to what’s out there and what’s needed in this industry,” she said. “I started playing around with chemicals and preservation techniques.”

In 2014, when her husband’s job moved them to Charlotte, which had no medical school, Decker took a job teaching anatomy at Central Piedmont Community College. She often used preserved body parts to teach her students.

She knew others could benefit from more hands-on exposure to anatomy, so two years later, she opened Experience Anatomy to make body parts available for teaching and training. It quickly became apparent that there was a greater demand for human tissue for making incisions and practicing procedures.

Experience Anatomy also offers specimens that schools can borrow to teach students about anatomy. The form of preservation, known as “plastination,” is most well-known for its use in the traveling Body Worlds exhibition.

In 2018, the company launched a foundation that could accept whole-body donations and spread the word to local funeral directors, hospice organizations and social workers. The foundation’s program is unusual because the bodies remain in its custody throughout the process, Decker said.

“Because we aren’t a so-called ‘body broker,’ we have more connection with the families,” she said. “Sometimes, we even hand-deliver ashes to them. We are really trying to change the image of the industry.”

Experience Anatomy opened its 5,000-square-foot cadaver lab in 2020. The company received about 120 whole-body donations last year, mostly from North and South Carolina. It now gets almost all of its tissue from its own donation program, Decker said.

New embalming technique

Traditionally, human tissue is preserved with formaldehyde, which has an off-putting smell you might remember from your high school science lab.

Experience Anatomy uses a proprietary soft embalming technique that Decker developed that leaves bodies soft and flexible, without the smell.

The technique has helped attract what has become Experience Anatomy’s bread-and-butter business: industry groups that use cadavers to train physicians and other health care providers on medical procedures and inserting medical devices.

Clients include well-known medical device companies, pain management clinics, EMS and fire departments, and the U.S. Department of Defense, which uses the cadavers for military surgical training. Decker said the lab’s annual revenues have doubled in each of the past few years.

Greensboro physician Scott MacDiarmid, who recently led a medical device training at Experience Anatomy, said it isn’t like most other cadaver labs, where odors can be nausea-inducing and fresh-frozen tissue sometimes deteriorates rapidly.

“Dating back to my days as a medical student, cadaver labs were like, ‘Eww, who wants to do that?’” he said. “Here, you come in, and the lab is beautiful and comfortable. The scent and the quality of the tissue is good. The cadavers really do mimic a human that’s alive.”

‘Meeting’ the donors at Dissection Club

Regardless of corporate demand, Experience Anatomy will continue to make hands-on anatomy accessible to all, Decker said.

To keep costs down for Dissection Club ($175 for a four-hour session), the lab relies on tissue previously used for medical training. Sometimes only portions of bodies are available.

But on the night The Ledger/NC Health News attended, two whole cadavers were laid out on gurneys: a man who was face down, and a woman who was face up, with a cloth covering her face.

After the participants donned gowns and two pairs of gloves, instructor Fauna Moore said it was time to “meet the donors.”

She led the class in a moment of silence to honor them, urging participants to be “gracious recipients of the gift.” She explained that every piece of tissue would be saved and cremated, and the remains returned to their families. “So we are just an extra step in the process,” she said.

The class reviewed a short medical history of each donor, and then Moore demonstrated how to carefully dissect layers of skin, fat and muscle using a scalpel and forceps.

“Take your time,” Moore said. “The slower you go, the more you will see.”

A far cry from anatomy textbook pictures

More than half of those present had attended the club before. They grabbed scalpels and went to work.

A reflexologist with an interest in plantar fasciitis focused on the foot and calf of the face-down donor.

Therapeutic massage therapist Karina Marquez, 29, painstakingly dissected the layers in the cadaver’s wrist and hand. Marquez said she was hoping to find ways to ease pain for one of her patients, who suffered from a disorder called trigger finger.

Moore walked around the room, pausing to share insight or a better technique. “That’s the medial nerve right there,” she told Marquez, pointing to a yellowish cord-like structure in the wrist. “It’s one of nine structures passing through this canal.”

Meanwhile, lab assistant Melanie Bebler guided a group on the other cadaver as they slowly exposed various anatomical structures.

The participants marveled at the amount of globby yellow fat they had to remove to get to the abdominal cavity, and several remarked that the tangle of organs and muscles they uncovered looked nothing like the colorful drawings in anatomy textbooks.

“It’s really hard to tell what’s what,” one said.

An unforgettable unveiling

Emily Button, 34, a medical massage therapist from Salisbury, said she felt a little queasiness when the class first started. “I kept reminding myself that it’s the shell, and the spirit is not there anymore,” she said.

As the session progressed, however, Button seemed to get more comfortable, eventually picking up a scalpel and doing some dissecting on an interior shoulder.

Hopkins, the massage therapist, said she was surprised at the spiritual dimension of the experience. “It makes you ask yourself, what is life? There is something that illuminates and animates tissue in life, and this makes me appreciate whatever that force is,” she said.

The session ended with an unforgettable moment — a look at the human brain. To get to it, Moore had to use a small power saw to cut through the skull. That may have been the most disconcerting moment of the night.

Participants in the Dissection Club fall silent as they gaze upon the human brain.

Finally, about 20 minutes past the session’s stated end time, and after much effort, Moore managed to pull off a section of skull, unveiling the brain. The room fell silent for the first time after four hours of near-constant conversation.

Together, the group peered at the folds and grooves of the brain, wondering at the mysteries of consciousness and cognition that make us human.

Michelle Crouch covers health care. Reach her at mcrouch@northcarolinahealthnews.org.

This article is part of a partnership between The Ledger and North Carolina Health News to produce original health care reporting focused on the Charlotte area. We make these articles available free to all. For more information, or to support this effort with a tax-free gift, click here.

Need to sign up for this e-newsletter? We offer a free version, as well as paid memberships for full access to all 4 of our local newsletters:

➡️ Opt in or out of different newsletters on your “My Account” page.

➡️ Learn more about The Charlotte Ledger

The Charlotte Ledger is a locally owned media company that delivers smart and essential news through e-newsletters and on a website. We strive for fairness and accuracy and will correct all known errors. The content reflects the independent editorial judgment of The Charlotte Ledger. Any advertising, paid marketing, or sponsored content will be clearly labeled.

Like what we are doing? Feel free to forward this along and to tell a friend.

Social media: On Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn.

Sponsorship information/customer service: email support@cltledger.com.

Executive editor: Tony Mecia; Managing editor: Cristina Bolling; Staff writer: Lindsey Banks; Business manager: Brie Chrisman