The case of the $10,000 colonoscopy

The following article appeared in the October 25, 2021, edition of The Charlotte Ledger. Sign up today for smart and essential local news in your inbox:

LEDGER IN-DEPTH

Dan Hurst’s medical procedure at Atrium Health cost thousands more than he was quoted. Despite a push for transparency, his experience reveals how medical pricing remains hopelessly complicated.

➡️ Plus: What you can do.

Dan Hurst, 63, received bills totaling nearly $10,000 for a February colonoscopy, several times the amount his doctor’s office estimated. His experience illustrates how consumers have a hard time getting straight answers on medical costs, which experts say inhibits shopping around and keeps prices high.

By Michelle Crouch

Dan Hurst, a retired engineer, knew he would have to pay out of pocket for the colonoscopy his doctor recommended. So before he went in for the procedure earlier this year, Hurst called Atrium Health Gastroenterology and Hepatology in Denver, N.C., and asked for an estimate.

The office told him the procedure would be about $1,500, plus lab charges. That was 50% more than Hurst had paid for his last colonoscopy in New York state, but he needed the procedure so he went ahead with it.

A few weeks later, he got the bill. The total? $9,988.

“I was shocked,” says Hurst, 63. “I thought it was a mistake. … It is unconscionable to dramatically underestimate the price of a medical procedure and then charge eight times the going rate.”

Hurst said nothing unexpected happened during the procedure. Most of the extra cost — about $5,300 — turned out to be a “facility fee” charged by Atrium Health Lincoln because Hurst’s procedure took place at a hospital-owned outpatient clinic.

Facility fees are one of many pain points for patients trying to predict and navigate their medical bills. Even as federal officials push for more transparency in healthcare pricing, Hurst’s story underscores just how difficult it can be for patients to get an accurate estimate of medical costs. It’s also a lesson in how dramatically healthcare prices can vary.

Atrium responds: Atrium Health Gastroenterology and Hepatology did not respond to a Ledger request for comment, but the office connected us to Atrium’s media relations department. In an emailed statement, Atrium spokeswoman Kate Gaier said she couldn’t discuss a specific case due to federal privacy laws, but she noted that giving any patient an accurate estimate in advance is difficult.

“Health care is very complex and, as a result, so is its billing,” she said. “There can be variables. For example, if an outpatient surgery takes longer than is typical or there is a complication discovered that has to be addressed, that can result in assessed costs being higher.” (Read her full statement here.)

Why it’s hard to get a straight answer on cost: When you buy most things, you can shop around and compare prices before you make your decision. But in healthcare, that’s nearly impossible.

That’s partly because there’s not just one price for a procedure. Instead, a third party — your health insurance company — negotiates rates for every possible medical procedure. Further complicating matters, each insurer negotiates different rates for those services. So it’s typical for a healthcare provider to charge many different prices for the exact same procedure, depending on a patient’s insurance plan.

In many cases, doctors and even practice managers don’t know the prices their offices charge, says Dr. Marty Makary, a surgeon at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and author of “The Price We Pay: What Broke American Health Care — and How to Fix It.”

Even if they did know, a bunch of other factors come into play that would still make it difficult for them to predict how much you would have to pay out of pocket: Have you met your deductible? Does your plan require preapproval? What will other providers such as anesthesiologists and pathologists charge? Are all of the providers in-network?

And as Hurst found out, location also plays a role.

“You can have the same doctor doing the same procedure but three different prices depending on where you have it,” says Michael Thompson, associate chair of the Department of Public Health Sciences at UNC Charlotte. “I’m an educated consumer and I understand the subtleties, and I still have trouble (predicting healthcare costs).”

Consumers face more health costs: It used to be that patients didn’t have to worry as much about paying for medical care because most health plans charged one co-pay amount no matter which provider you saw. These days, due to the growing prevalence of high-deductible health plans, people are on the hook for more of their healthcare costs.

Hurst says he ended up on a high-deductible plan (with a $5,000 deductible) because he retired before he was eligible for Medicare and lost his employer-sponsored health insurance.

“I knew I had lousy insurance. I told them I expected I would have to pay the entire amount out of pocket. That’s why I called to ask about the cost,” he explains. “If they had given me any inkling that there could be additional fees, I would have dug into it much further.”

Loophole in insurance coverage: During a colonoscopy, a screening test for colon cancer, a doctor uses a probe to examine the patient’s bowel for pre-cancerous polyps and removes anything suspicious. Because it is preventative, the procedure is supposed to be fully covered by insurance companies under the Affordable Care Act, with no copay or deductible.

But there’s a catch. U.S. health agencies recommend a colonoscopy once every 10 years. If you’ve ever had a polyp removed, doctors usually recommend more frequent screening, because you’re at higher risk for colon cancer. In that case, insurers aren’t required to fully cover the cost. That means that unless you’ve met your deductible, you have to foot at least some of the bill.

Hurst had a polyp removed during a previous colonoscopy, so he knew he would be on the hook for most or all of the cost of this one.

Double the average price: NewChoiceHealth, a website designed to allow consumers to compare the costs of common medical procedures, says the national average cost for a colonoscopy is $2,750.

However, prices can vary wildly. One analysis published in August found that the median insurance-negotiated price for one specific type of colonoscopy ranged from $44 to almost $28,000.

What tripped up Hurst is that he didn’t realize that his physician’s office was quoting only its charge for the colonoscopy (which was ultimately $911 after insurance repricing). He also didn’t realize how much the location of his procedure — in a hospital-owned outpatient surgical facility — would raise the cost.

Watch out for facility fees: Hospitals have long been allowed to charge facility fees to cover the overhead of offering services such as a 24-hour emergency room that “are expensive to operate but provide a community benefit,” Thompson explains.

In recent years, however, more patients are being hit with the fees, even if they never walk through the door of a traditional hospital building, Thompson says. That’s because healthcare systems such as Atrium have been buying and opening physician practices, urgent care clinics and outpatient surgery centers. If you have a procedure in one, a healthcare system can legally charge a facility fee.

Atrium’s Gaier said facility fees are tied to the level of care at each facility:

Where you receive care matters … Receiving care in a trauma center is more expensive than in many other parts of a hospital. Care in a hospital is more expensive than in a physician’s office or an outpatient facility. This is largely due to the governmental requirements of each type of facility, in terms of staffing and equipment that has to be available at all times.

No option for a doctor’s office procedure: Hurst says he asked about having his colonoscopy without anesthesia, as he did with two previous colonoscopies in Rochester, N.Y. The total cost for each of those colonoscopies was under $900. However, Atrium Health Gastroenterology and Hepatology was unwilling to do the procedure in a doctor’s office and insisted upon anesthesia, Hurst says.

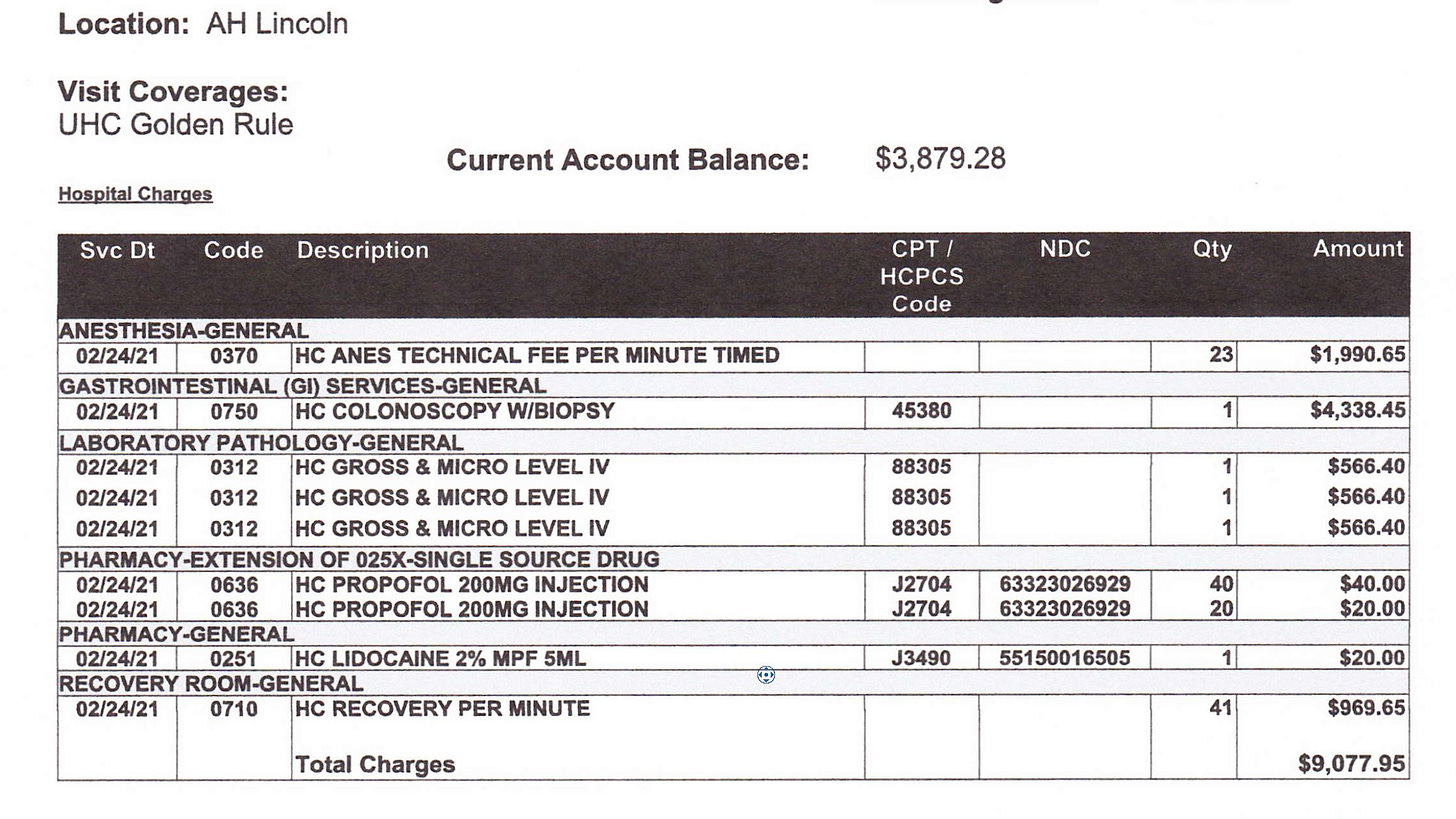

The office scheduled Hurst to have his colonoscopy at the Atrium East Lincoln surgery center, which is not attached to a hospital. The center charged Hurst $1,990 for anesthesia, $1,698 for pathology, $969 for 41 minutes in the recovery room ($23 a minute) and $4,338 simply for having the procedure in the building, along with some smaller charges. The total bill from the center was $9,077, in addition to a $911 charge from Atrium Health Gastroenterology and Hepatology to cover the doctor’s time, according to bills Hurst shared with The Ledger.

‘Shocked’: Hurst says he thought the total charges for his colonoscopy were a mistake until Atrium sent him the breakdown of costs above. Those costs were in addition to a $911 charge from his doctor.

Hurst said an Atrium billing representative later told him he would have saved thousands of dollars if he had elected to have the same procedure at an Atrium-owned ambulatory service center (ASC), rather than a so-called hospital outpatient surgery center. He says nobody pointed out that option before the procedure.

Pushing for more transparency: Many experts believe forcing hospitals to publish the varying rates they charge insurance companies for medical goods and services could help patients better predict healthcare costs. Making the information public should also increase competition and drive down costs, Makary says.

To that end, the federal government last year issued new rules on price transparency that are supposed to help Americans “know the cost of a hospital item or service before receiving it.”

The rules, which went into effect in January 2021, require hospitals to post “a consumer-friendly display” of prices they’ve negotiated with insurance companies for 300 common procedures that can be scheduled in advance, including colonoscopies. Hospitals are also supposed to publish a machine-readable file with the prices of every service they offer.

However, a study in July found that 94% of hospitals, including Atrium and Novant Health, weren’t fully meeting the requirements. (Atrium’s problem was that it did not include discounted cash prices in its machine-readable file, the report said. A researcher said on Oct. 6 that the file still does not include those prices.)

Hospitals offer “cost estimators”: Even hospitals that complied rarely published an actual list of prices, says Cynthia A. Fisher, founder of Patient Rights Advocate, the group that conducted the study. Instead, many created cost estimators that spit out a projected price after a patient answers questions, including the name of their health insurance plan. Both Atrium and Novant have taken that approach.

Fisher says the estimators undermine the spirit of the transparency rule by making prices visible only to a given patient.

“The beauty of a data file of 300 actual prices in a spreadsheet is that … there would be an opportunity for all of us to see the wide price variations, and then competition and consumer choice would drive down these healthcare costs,” she explains.

How it plays out in real life: To find what would happen if a patient like Hurst were shopping around for colonoscopy prices, the Ledger conducted a real-world test.

First, we tried Atrium’s online cost estimator. It didn’t work because Hurst’s insurance isn’t common and wasn’t listed as an option.

Then, we called Atrium Health Gastroenterology and Hepatology — where Hurst had his procedure — and asked for the cost of a colonoscopy with Hurst’s insurance coverage. The first woman who answered the phone said the standard fee is $1,400 but “I don’t know what’s going on with your colon, so I can’t tell you for sure. It depends what they find.”

The woman didn’t mention additional fees, but when The Ledger asked, she acknowledged there could be hospital or anesthesia costs, adding she had no idea what those would be. Is there any way the total could come close to $10,000? the Ledger asked. “Oh no,” the woman said.

“Hello, this is priceline.” When The Ledger called the office on another day, again a facility fee wasn’t mentioned until we asked. That time, when we pressed for details, we were transferred to Atrium’s priceline, a number dedicated to patient billing questions. The priceline representative immediately asked for the five-digit insurance (CPT) code, which we didn’t have.

The Ledger called the gastroenterology office back to get the code, and the office gave us six different numbers, saying there was no way to know which was correct until after the procedure. Back at priceline, a representative said those codes had fees ranging from $8,157 to $24,196. The agent stressed that the insurer-negotiated rates are likely much lower, but she would not disclose those unless I gave her the patient’s date of birth and specific insurance information. She said patients without insurance are typically offered 50% off the total.

Fisher, of Patient Rights Advocate, says keeping healthcare pricing complex allows the healthcare and insurance industries to continue to overcharge.

“Why do only the insurance industry and hospitals object to price transparency? It’s because they can continue to make outrageous returns if the consumers are blind,” she says. “They use clouds and curtains to make it appear to be complex when it’s actually quite simple.”

Be a smarter patient: Most Americans still aren’t in the habit of asking questions and comparison shopping before we schedule medical care, increasing the chance we’ll be surprised and frustrated when we get big bills. If your doctor is recommending a non-urgent procedure, taking these steps can help you be more informed and lower your medical costs:

Compare prices on a third-party site: Tech firms are using the new hospital pricing data to build tools designed to make it easier to compare prices across healthcare systems. Before you schedule a procedure, check Turquoise Health to see which locations have the lowest prices under your insurance. (Other sites including Firelight Health and My Medical Shopper are in the works.)

Ask for written estimates: Ask both your physician’s office and your insurance company for an estimate of your likely out-of-pocket cost for a procedure, and compare them to each other.

Specifically ask about facility fees. Find out if you will be charged a facility fee and what that fee will be. If there is a facility fee, ask if it’s possible to move your procedure to a different location. You’re less likely to encounter facility fees if you receive your care at a center that isn’t owned by a hospital.

Offer to pay in cash: In many cases, providers will offer significant discounts if you’re willing to make an upfront cash payment rather than using your insurance coverage, Fisher says. One study found cash prices for healthcare services are on average 39% lower than insurer prices. (The downside is that what you pay won’t count toward your deductible.)

Ask your physician only to use labs and providers that are in-network: Make it clear to your doctor that you want to avoid out-of-network charges. Your insurance company can help you identify labs and facilities in your network.

Negotiate. Use Turquoise Health or Fair Health to find out what other providers are charging, then use those prices to ask for a discount even before you agree to a service or procedure.

Threat of collections: Hurst’s insurance kicked in to cover part of his colonoscopy bill because he met his $5,000 deductible. After a $911 payment to the gastroenterology office, he still owed Atrium $3,879.

Hurst says he made many phone calls to fight the remaining balance, and a billing supervisor eventually agreed to reduce it by about 50%, because he wasn’t informed of the total cost.

Hurst continued to protest until Atrium finally said it was going to turn the debt over to a collection agency.

At that point, Hurst paid. In a letter he included when he mailed the $1,829 check, he wrote: “By using threats of turning me over to collections agencies and damaging my credit rating and hard-earned financial standing, you are successfully extorting me for money you earned through deceit, fraud and fraudulent misrepresentation. Congratulations! Here’s your extorted funds.”

Michelle Crouch is a freelance writer and a regular contributor to The Ledger who often writes about healthcare. Send her story tips at michellecrouchwriter@gmail.com.

Need to sign up for this e-newsletter? We offer a free version, as well as paid memberships for full access to all 3 of our local newsletters:

➡️ Learn more about The Charlotte Ledger

The Charlotte Ledger is a locally owned media company that delivers smart and essential news through e-newsletters and on a website. We strive for fairness and accuracy and will correct all known errors. The content reflects the independent editorial judgment of The Charlotte Ledger. Any advertising, paid marketing, or sponsored content will be clearly labeled.

Like what we are doing? Feel free to forward this along and to tell a friend.

Executive editor: Tony Mecia; Managing editor: Cristina Bolling; Contributing editor: Tim Whitmire, CXN Advisory; Contributing photographer/videographer: Kevin Young, The 5 and 2 Project