This Memorial Day, he remembers fighting Hitler's army

Plus: Ledger members are invited to send in questions about huge CMS construction plan; Tryon Medical's CEO throws shade at Atrium merger; Pricey apartment sale in SouthPark

FOR MEMORIAL DAY: On Fridays, readers who have signed up for our free Ledger newsletter typically receive an abbreviated version of our articles. Today, we’re making our entire Friday newsletter free for all, because it contains an article that’s a Memorial Day tribute to those who have served our country. We can feature articles like this one by talented local writers because of the support of our Ledger members.

Won’t you consider becoming one today? For $99/year or $9/month, you can support our efforts to improve local journalism. Join today.

Good morning! Today is Friday, May 27, 2022. You’re reading The Charlotte Ledger, an e-newsletter with local business-y news and insights for Charlotte, N.C.

Editor’s note: In observance of Memorial Day, we won’t be publishing newsletters on Saturday and Monday. We’ll be back in Ledger members’ mailboxes Tuesday for the Ways of Life newsletter, and our flagship Charlotte Ledger newsletter will return for everyone on Wednesday.

Memorial Day weekend is a time to honor the military heroes who died in service to our country. So today we present the story of Bob Welsh, a 99-year-old World War II veteran from Charlotte who remains grateful that he was able to return home after the war — and whose memories of battle are still fresh, more than 75 years later. We hope you enjoy his heroic and inspiring stories of service — stories that are getting ever-more difficult to capture, as the number of World War II veterans dwindles.

Bob Welsh, 99, went from Davidson College to a foxhole in Germany, then met his wife after the Nazis surrendered; ‘I’m a lucky man. What a life I’ve had!’

At age 99, Bob Welsh still paints and writes poetry, inspired by his service in World War II. In this photo taken last month, he stands in front of a portrait he painted of his late wife Marlis, who died in 2020. (Photo by David Perlmutt)

By David Perlmutt

In the end, after months of unrelenting combat in the snow and brutal cold of the Battle of the Bulge, escaping bursts of German burp guns, foot mines and grenades, and finally the grinding town-to-town fight through Nazi Germany, Bob Welsh stood atop his Army tank bracing for more battle.

But on that early May evening in 1945, in a field in eastern Germany near Czechoslovakia, no battle came. Just silence, except for a lone voice blaring from the BBC in London, delivering the wondrous, at first ungraspable, news: World War II in Europe was over. The Germans had unconditionally surrendered. Adolf Hitler was dead.

Over the broadcast, Welsh and other soldiers from the 87th Infantry Division could hear crowds of Londoners cheering. But as the news sunk in, so, too, did a profound reckoning:

“We had no booze. No women,” Welsh, a long-retired Charlotte society photographer, mused 77 years later with a shrug. “There was no celebration — nothing we could do but sit there in complete silence. We were grateful for our good fortune. We’d made it. A lot of our guys didn’t.”

On this Memorial Day weekend, Welsh, at six months shy of age 100, remains ever grateful, defying the last battle facing World War II veterans: time. He is among the estimated 225,000 Americans — of more than 16 million — who served in that war and are still left to their memories and battle scars.

His memories are vivid, etched on the mind. Many nights, he wakes with a thought — a nudge from the deep past — and climbs out of bed in a Charlotte retirement community for his nearby computer. He may spend hours writing poetry or prose about his battles, or the absurdities of war, about politics or religion, or about Marlis, his beloved German-born wife of 73 years who died in 2020 at nearly 94.

Or he might paint a portrait of Marlis, or his three children and four grandchildren. Welsh walks without a cane. He still keeps a calendar, filled with garden parties, weekly bridge games and rounds of golf when son George visits from Louisiana.

Yet Welsh knows the holiday is not meant for people like him — the survivors. “It’s to honor those who didn’t come back,” he said. “I’m still here — and at 100 almost! I know I’m a lucky man. What a life I’ve had!”

It ‘was God’s providence’

It’s a life worth telling. It began in Muskogee, Okla., in November 1922, then Oklahoma City and Tulsa, as his World War I veteran father George, a Travelers Insurance salesman, advanced in the company. Bob was in high school in 1939, when Travelers moved his family of four to Charlotte and George into a management job overseeing the Carolinas.

After his senior year at Charlotte’s old Central High, Welsh enrolled at Davidson College to study science. He joined a fraternity and ROTC.

In June 1943, war raging in Europe, Welsh was a junior when the Army plucked him and several Davidson ROTC students for Officer Candidate Training. They were sent to basic training in Georgia, where they learned to shoot the .37mm anti-tank gun. They were assigned to the 87th Infantry Division, part of Gen. George Patton’s Third U.S. Army — Welsh as a rifle platoon leader — and shipped to England in September 1944, on the Queen Mary.

It was three months after D-Day, the invasion at Normandy, France through Hitler’s Atlantic Wall to liberate Europe from the Nazi grip.

In early December, Welsh’s K Company was loaded into eight boxcars, bound for Metz, France, and the front line. Welsh, a second lieutenant, soon witnessed what war could do, leading his platoon up a ridge strewn with a dozen dead Americans (“still in their overcoats”) outside Obergailbach in northeastern France.

“Seeing those bodies, you talk about scared,” Welsh said, his voice trailing off.

A week later on Dec. 13, 1944, they were in foxholes near Gersheim, Germany, when German artillery shells started falling, aimed at tree tops to shower splinters and shrapnel on the Americans.

Suddenly, shrapnel slammed through logs covering Welsh’s foxhole and he felt a terrible pain in his knee.

“Wow, call the meat wagon (ambulance)! I’ve been hit!” he shouted. But examining his knee, he saw a “steaming, hot piece of smoking metal” stuck in the foxhole wall and realized it had sliced a log that clobbered him. “Call off the medics!” he shouted again.

Welsh was on the phone updating the battalion command post when he spotted 50 Germans approaching. Before he could request artillery, the phone died — the wire connecting it to the command post had been sliced. Spliced back together, Welsh heard a calm voice: “This is Cannon Company.”

In no time, an American phosphorous bomb exploded at the coordinates Welsh supplied. The Germans fled. “For those two (phone) wires to be in the same place and hook us straight into Cannon Company was God’s providence for sure,” he said.

Leading platoons and ‘tiger patrols’

Welsh would experience “God’s providence” many times in war — and life.

Three days after Gersheim, the 87th was hustling to Belgium. The Battle of the Bulge, Hitler’s final card, a massive counterattack in the Ardenne region between Belgium and central Luxembourg, was on in earnest.

Paris and St. Lo had been liberated. American and British troops were poised to pierce the Siegfried Line, the massive barrier protecting Germany’s western border. Allied planes were bombing Berlin.

But in a surprise attack, Hitler threw 250,000 troops at the middle of the 85-mile-long Allied front, creating a bulge meant to divide the American-British alliance into chaos and repel an invasion of Germany.

Gen. Dwight Eisenhower ordered a half-million men into the battle. The brutal winter made the fighting more perilous. “The enemy and the weather could kill you — a bad combination,” Welsh said.

Patton turned his 30,000 troops north for Bastogne, in southwestern Belgium, to hit the Germans from the south. The city was a critical crossroads where American 101st Airborne paratroopers were ill-clothed, short on food, ammunition and medical supplies — and badly outnumbered.

Welsh had his platoon loaded up, but before they could leave, a major ordered Welsh and his sergeant to rescue two Americans from another company stranded on a hill.

By the time Welsh got back with the two rescued soldiers, everyone was gone. They started walking and soon found a factory with Americans eating inside. They hitched rides to Pironpre, Belgium, near Bonnerue where the 87th had assembled.

Welsh thought he’d get his platoon back, but a colonel told him he’d been replaced. “They thought I was missing, or I’d been killed,” he said.

Instead, he volunteered to lead a 10-member “Tiger Patrol” to engage the enemy on nightly patrols, take prisoners to interrogate and disable Tiger tanks.

The patrols were fraught with danger, often spending more time behind German lines than their own. They slept during the day and rooted out the enemy at night. They were given only a bazooka to take down heavily armored tanks.

Patton wanted to hit the Germans on Christmas, but days of overcast skies, snow and fog grounded American bombers and cargo planes loaded with supplies. Impatient, Patton ordered a chaplain to send a prayer to God for clear skies.

“It took no time for word to get to the front line that Patton himself had ordered God to clear the sky,” Welsh said.

The skies cleared on Dec. 26. Patton unleashed his forces, and American bombers and cargo planes bombed Germans and resupplied troops in Bastogne. The 87th Division attacked a German armored tank division in Bonnerue and nearby Moircy and Tillet.

The Germans retreated.

Yet it’d take another month to recapture dozens of towns in Belgium and Luxembourg lost in the German blitzkrieg.

It was hardly ‘easy work’

By early February 1945, the Americans were threatening to crack the 390-mile-long Siegfried Line, stretching from the Netherlands to Switzerland, with 18,000 bunkers and tank traps called “Dragon’s Teeth.” Shortly before the attempt, Welsh was transferred to the cavalry division — typically “easy work.” But Welsh was one of the few patrol leaders who wasn’t dead or wounded. He was ordered to lead the Task Force Muir, an “all-out assault” through Germany.

In an armored car, Welsh led a convoy of heavy and light tanks, artillery, trucks and infantry five miles long through the Siegfried Line, bound first for Koblenz, Germany, an important crossing point where the Moselle and Rhine rivers meet.

One morning at sunrise, the convoy roared into Lissendorf and caught the Germans off-guard. The Americans needed the town’s bridge over a tributary of the Moselle, but townspeople waiting for rations blocked their access. Welsh told his sergeant not to shoot, but he fired his machine gun over their heads — “total disobedience,” Welsh said. “We got 100 yards from the bridge when the Germans blew it up and sent basketball-size boulders down on us.”

Days later in a village halfway to Koblenz, Welsh was in his armored car when he felt a “white hot” .88mm shell zip inches past his ear. He instantly fired his machine gun toward the Germans, which brought more .88s. The convoy retreated. “We had engaged the enemy,” he said. “That was our job.”

His commanders didn’t see it that way. They removed Welsh from the lead car, thinking he had led them into an ambush. He spotted a tank mired in the middle of a field with a sergeant yelling into his radio that he wouldn’t move until he got a machine gunner replacement.

“I climbed aboard and told him: ‘Hey, I’ll be your machine gunner.’ I didn’t know bean squat about tanks.”

In Koblenz, the Americans found the city unbombed and empty. “The Germans were hiding in cellars, and the infantry following behind caught hell.”

As they ground through Germany, the fighting slowed and finally, on May 7, 1945, Welsh stood in the gun turret of his light tank outside Plauen, near the Czech border, when it ended.

But not his military duty.

A wife and a top-secret job

After a two-week leave in France, he was folded into occupation forces. He was assigned to the 4th Armored Division and sent to Regensburg in southeastern Germany.

One night, he and a friend walked into a club reserved for majors and colonels in a hotel looking “for booze and women.” It was empty, except for two English-speaking German sisters. One was Marie-Luise Osmers, who called herself Marlis. Welsh was smitten and asked her out.

She told him she got off at 9 p.m. At 8:55 p.m., he returned to find Marlis running out “trying to duck me.”

He ran after her.

By that time, Welsh was assigned to an Army post outside Regensburg guarding the Czech border. Days later, Marlis and her sister were transferred there to open a library and doughnut shop.

After weeks of dating, they found a preacher to marry them but were told U.S. law forbade Americans from marrying Germans. They unofficially exchanged vows.

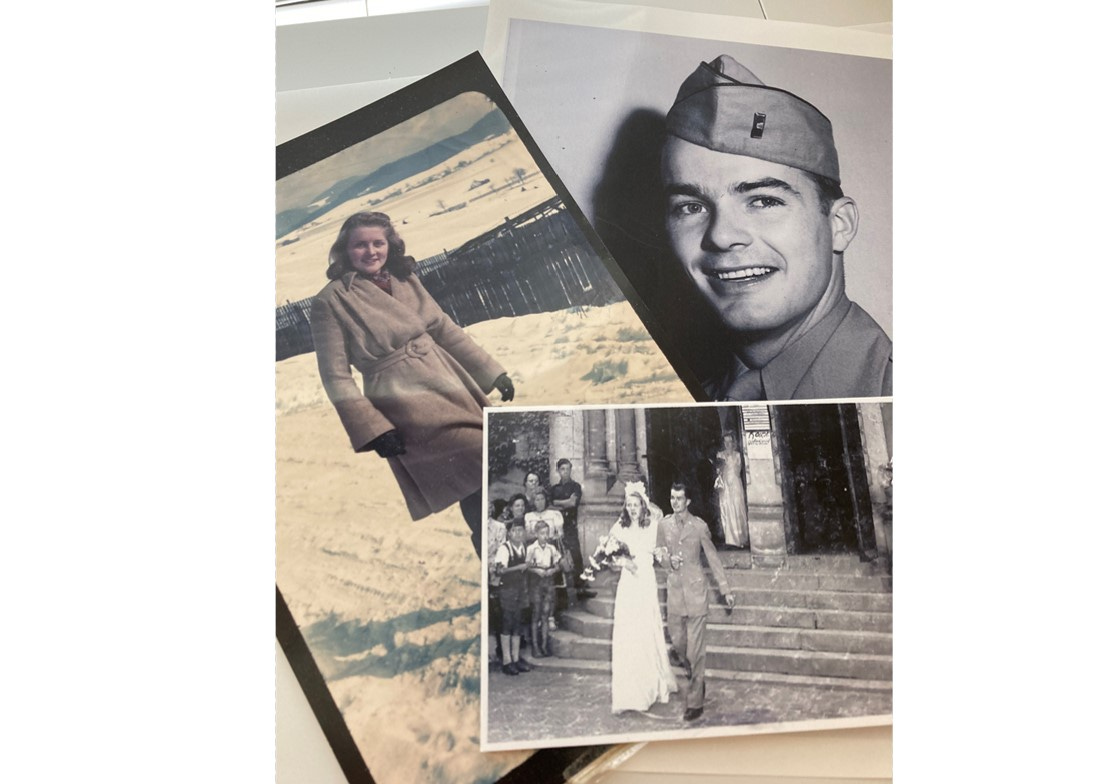

Bob and Marlis Welsh married in Germany, then settled in North Carolina, where Bob finished his undergraduate studies at Davidson and then got his law degree at UNC Chapel Hill. He went to become a popular society photographer in Charlotte. (Photos courtesy of Bob Welsh)

Soon Welsh’s military tour was over, but he re-enlisted before leaving Germany, intending to come back. He spent six months at Fort Hood in Texas, with a visit or two to Charlotte.

He returned to Germany — and Marlis — and was given a new job. It was a top-secret mission called Operation Paperclip to recruit German scientists, many of them Nazis, to America, where leaders wanted them for their chemical and biological weapons research and to help develop the U.S. rocket program. They included space architect Wernher von Braun.

Welsh was sent to Landshut, where the scientists and their families were processed. The city, 40 miles south of Regensburg, was also where Marlis and her parents lived.

He and a driver picked up a dozen scientists and their families and escorted them to be processed, then to an airport to fly to the United States. The most famous among his 12 was Hugo Eckener, the German dirigible designer who worked with Goodyear on its blimps.

In 1947, Welsh and Marlis married in a “real wedding,” the church packed with townspeople. Welsh’s aunt, Aleta Brownlee, who worked for the U.N. reuniting displaced children with their families, was the lone relative able to attend.

‘Still making people mad’

The newlyweds left Germany for North Carolina later that year, bringing with them their first-born, daughter Katherine. Discharged with a Bronze medal for bravery, Welsh finished his last year at Davidson and then two years of law school at UNC Chapel Hill.

As a boy, he’d shot photos with his father. To make money for his growing family while studying law, he started photographing weddings and events. He liked it, quit law school and moved his family to Charlotte, where in 1950 he opened the Bob Welsh Photography Studio that he ran for 50 years.

He’d survived the battlefield unscathed, except for combat stress that led to drinking — and nightmares. One night, Welsh, 35 then, told Marlis he thought he was going to die.

But in 1995, 50 years after VE Day, he got a call from a man in his unit, who told Welsh a sergeant had threatened to kill him: “He said I was always getting us into situations we couldn’t get out of.” That led Welsh to write a 1998 novel based on his battles called “Two Foes to Fight” — and “complete catharsis.”

Two years later in 2000, he and son George toured his battlefields. “The foxholes were still at Pironpre,” he said. The nightmares didn’t return.

Longevity is not a family trait. His father, George, died at 64; his mother, Muriel, at 78. His sister Jean Eason, two years older, died in 2006 at 85. “I’m the oldest in my family — ever,” he said. He’s chalked it up to “good booze and a wonderful wife — she was a woman and a half!”

When Marlis died in 2020, “we were both ready to go,” he said. “But I’m still here, waiting — still making people mad.”

David Perlmutt has written about the Carolinas for 40 years, including 35 years he spent as a reporter for The Charlotte Observer. Reach him at davidperlmutt@gmail.com.

Huge CMS construction plans are in the works. What questions do you have about what’s ahead?

On Tuesday, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools officials unveiled a massive $5.2B plan that would fund 125 major projects across the district over the next 10 years. Included the proposal, which is still in its early planning stages, are demolishing and rebuilding dozens of schools all across the district, creating several new high schools that focus on specific areas of study and potentially rolling out big high school regional athletic campuses. (You can read all about it in a comprehensive article we published on Wednesday. You can also download and read the plan here — but be warned that it’s a large 99MB file)

We’ve got some questions about how officials are planning for future CMS facilities needs, and the national trends that may be going into their decision making. We’re guessing you have questions, too.

Here’s the good news: Dennis LaCaria, a schools facility consultant who is working with CMS on its plan, has agreed to answer our questions in a special question-and-answer session with The Ledger next week.

✉️So, if you’re a paying Ledger member, feel free to email us with your questions about CMS’ latest plan for growth, and we’ll ask them on your behalf and publish the answers next week in The Ledger.

We periodically like to extend special perks to Ledger members (whose membership dollars are what keep the Ledger afloat) — and this is one of those perks. If you’re not already a Ledger member, why not join today?

In brief

SouthPark apartments sale ranked #2 in N.C.: The new 203-unit Hazel SouthPark luxury apartment complex sold this week to Lincoln Property Co. of Virginia for $130.75M, or about $644,000 per unit, according to property records. The sale by developer ZOM Living is believed to be the state’s second most expensive apartment-complex sale on a per-unit basis, behind only the sale of The Hawk in South End in December, which fetched $683,000 per unit, according to real estate data company CoStar.

Proposed hospital merger criticized: The CEO of Tryon Medical Partners criticized Atrium Health’s proposed merger with Advocate Aurora Health on Thursday, saying studies show hospital consolidations escalate costs and prices. Dr. Dale Owen said on WFAE’s “Charlotte Talks with Mike Collins”: “I can’t figure out who’s really benefiting. If the cost goes up and price goes up, there are no shareholders and the tax base goes down, who is really benefiting from this? It seems to me it’s more likely to be the hospital executives and contracting agents with the hospital system.” Atrium has said the merger, which would create one of the largest nonprofit hospital systems in the country and is under regulatory review, would benefit patients and communities. (WFAE)

BofA workers offered electric vehicle perk: Bank of America is offering employees who have been with the company at least three years and have salaries of less than $250,000 a one-time, $4,000 reimbursement toward the purchase of an electric vehicle. It’s also giving raises to workers who make less than $100,000. (Reuters/Bloomberg)

N.C. births rise: The number of births in North Carolina rose last year by 3%, compared with 2020. It’s the first yearly increase since 2014. The number of births plunged during Covid but rebounded in 2021 to higher than pre-pandemic levels. (Axios Raleigh)

Busy Memorial Day weekend at the airport: Charlotte’s airport expects its busiest days this weekend to be today and Monday, with an estimated 31,000 local passengers starting their trips. It’s slightly fewer than the 33,600 who traveled from the airport on Memorial Day weekend in 2019, before the pandemic. (Fox 46)

Controversial bill passes N.C. Senate committee: A Republican-backed bill that would limit the ability of schools to teach children in grades K-3 about sexual orientation or gender identity passed an N.C. Senate education committee on Wednesday. It also requires schools to notify parents “prior to any changes in the name or pronoun used for a student.” Republicans call it a “Parents’ Bill of Rights,” while Democrats say it’s similar to a Florida measure that opponents have dubbed a “don’t say gay” law. Read the bill for yourself here. (It’s unlikely to become law in N.C.)

Students behind academically: Students in North Carolina fell behind academically between two and 15 months on average while learning remotely in the first year of the pandemic, according to new estimates from the state Department of Public Instruction. Many students will need intensive academic intervention to close the gap, the report said. (WRAL)

Steve Smith’s prank: Former Panthers receiver Steve Smith pranked football fans Thursday by posting a video on Twitter in which he said he was “officially” joining the coaching staff of the New York Giants. He later said it was a joke and added: “It’s May, but I definitely got you like it was April. … All you folks that thought that was happening, gotcha!” (New York Post)

Lifeguard shortage: Mecklenburg County is struggling to find lifeguards for its pools and public beach. Only 196 of around 250 lifeguard jobs have been filled, a county official told The Observer. The article did not address whether any public or private pools would have to be closed this summer because of the lifeguard shortage. (Observer)

License revoked: The N.C. Medical Board revoked the license of Charlotte psychiatrist Dr. Patricia Boyer after finding that she had an intimate relationship with a patient that spanned more than a decade and that she provided the patient medication without medical documentation. (Observer)

Car shop owner retaliates: The owner of a car repair shop who has been feuding with neighbors in Waynesville, three hours west of Charlotte, over the location of parked cars has apparently retaliated by hanging a sign on the property that is causing a stir. It says it is the “future site of The Hoochie Hut,” although strip clubs are not allowed in the county. “He got so mad that we think this Hoochie thing is a retaliation on his part,” the secretary of the nearby homeowners association said. (The Mountaineer)

Need to sign up for this e-newsletter? We offer a free version, as well as paid memberships for full access to all 4 of our local newsletters:

➡️ Opt in or out of different newsletters on your “My Account” page.

➡️ Learn more about The Charlotte Ledger

The Charlotte Ledger is a locally owned media company that delivers smart and essential news through e-newsletters and on a website. We strive for fairness and accuracy and will correct all known errors. The content reflects the independent editorial judgment of The Charlotte Ledger. Any advertising, paid marketing, or sponsored content will be clearly labeled.

Like what we are doing? Feel free to forward this along and to tell a friend.

Social media: On Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn.

Sponsorship information: email brie@cltledger.com.

Executive editor: Tony Mecia; Managing editor: Cristina Bolling; Contributing editor: Tim Whitmire, CXN Advisory; Contributing photographer/videographer: Kevin Young, The 5 and 2 Project

Why is a law that stops adults outside the family from discussing sex with 5-8 year old's controversial? The Ledger should not normalize grooming