What is Blue Cross Blue Shield NC up to?

Insurance commissioner blasts plans that he says could raise premiums

IN-DEPTH

A bill in the N.C. House would grant the state’s biggest nonprofit insurer broad leeway to operate like a for-profit company. But what it’s really after—or what it might mean for customers—remains elusive.

By Rose Hoban

This article is a collaboration among NC Health News, The Assembly and The Charlotte Ledger.

For 90 years, Blue Cross NC has been a constant in the state: the largest health insurance provider across all 100 counties, a ubiquitous advertising and philanthropy presence, and one of the most influential political actors in the state.

Now, after a high-profile contract loss this winter, the nonprofit health insurance carrier is asking lawmakers for a serious and potentially far-reaching change to state regulations so that it can behave more like national for-profit competitors.

On Monday, North Carolina Insurance Commissioner Mike Causey came out swinging against the bill, taking a fight that has been brewing inside the General Assembly this spring to the broader public.

“I think that this legislation is missing many provisions that's necessary to protect the people, the policyholders,” Causey said. “[It] does not provide for a meaningful review of reorganization.”

Ahead of Causey’s remarks, the screen behind him had displayed a slide that proclaimed in large letters: “This bill is about corporate greed.”

Proponents argue it would level the playing field, but skeptics say a lack of transparency could bring serious uncertainty for the more than 4 million North Carolinians whose insurance cards bear the name “Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina.”

“Under today’s corporate structure, they can't move fast and in the world of business, you have to be able to move fast when it comes to opportunities,” Rep. John Bradford, a Republican from Cornelius and lead sponsor of a bill to make the changes, told the House Health Committee in late March. He argued that the increased regulatory hoops the company has to jump through as a nonprofit slows it down.

Executives, lobbyists and spokespeople for the insurer, which has $7.7 billion in assets (including $4.5 billion in reserves), maintain that for the most part, nothing would change for consumers. They emphasize that the move would allow the company to be more “nimble,” “flexible,” and “competitive.” The company is undertaking a full-court press at the legislature, with 14 lobbyists working to make the case for House Bill 346.

Blue Cross NC’s ties to the state are widespread and prominent. Many journalism organizations receive advertising dollars from the company, including The Assembly. NC Health News has been a grantee of the Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina Foundation since 2020.

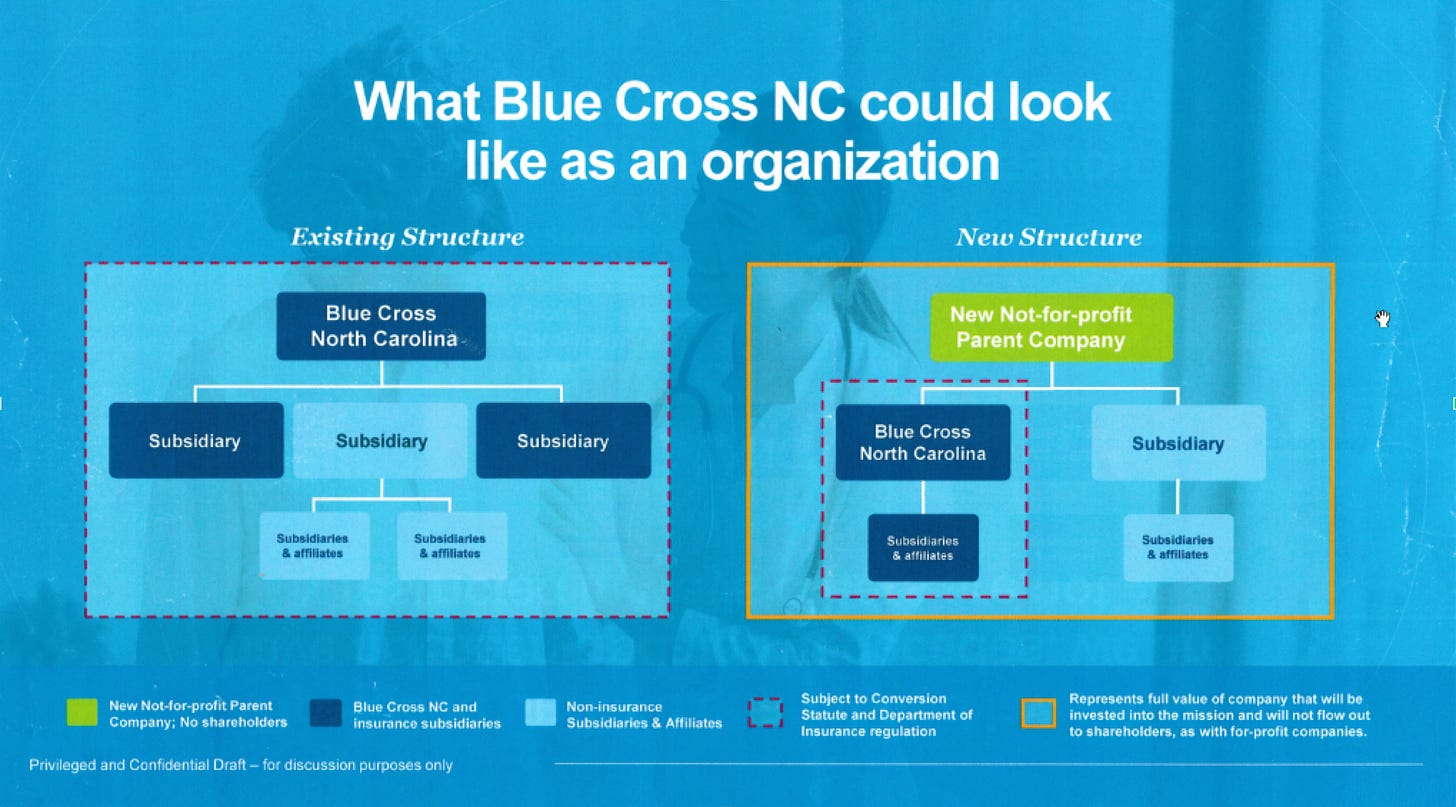

Introduced in mid-March, the bill would allow the company to create a nonprofit parent holding company for Blue Cross NC and any other for-profit subsidiaries. That holding company—essentially a shell company with the same executive team as the insurance entity—could take money built up by the company’s insurance business and “use that money, basically, however, they want to use it,” said Jackie Obusek, the chief deputy commissioner of the state Department of Insurance.

“Even with simple corporate transactions, the devil’s in the details,” Causey said during his press conference. “With this bill, the devil’s in the lack of details.”

He also expressed his belief that if the bill were to pass, it would raise premiums for North Carolina policyholders.

Blue Cross NC says it will use the money to purchase companies that can improve the services they offer policyholders. But such purchases would come with almost none of the regulatory oversight the company currently receives from the state Department of Insurance. And Blue Cross NC has been vague about the companies that it would buy.

The House bill has 56 sponsors, out of a total of 120 members. Thirty-six state senators out of 50 have sponsored an identical bill filed in that chamber. The House bill is scheduled to be discussed in the House Health Committee, where lawmakers will get a look at a bill that’s been heavily marked up since it was first introduced in late March.

Health care advocates, some key legislators and Causey remain skeptical, even of the amended bill. In interviews, lawmakers, health economists, and attorneys all questioned Blue Cross NC’s stated intentions. They stressed their belief that restructuring would bring harm and not benefit the taxpayers and premium payers who funded the company for decades. House Health co-chair Rep. Donna White, a Republican from Johnston County, spoke after Causey at his press conference and said her phone has “absolutely burned up” with people contacting her to oppose the bill.

Another skeptic is Rep. Donny Lambeth, a Republican from Winston-Salem, co-chair of the House Health Committee, and a retired hospital president.

“‘Look, guys, you’re big. You've done a lot of good things in North Carolina, but people are concerned with your size and what you're up to,’” Lambeth said he told the company’s lobbyists. “You've got to be able to answer what is it that you're up to. Because people don't trust Blue Cross. I'm just laying it out flat.”

Largest share

A group of physicians created Blue Cross NC as a nonprofit in the 1930s, allowing it to build up assets tax-free until the mid-1980s, when a change in federal law meant that the company had to start paying corporate taxes.

As a nonprofit, Blue Cross NC has to answer to the needs and priorities of premium payers, rather than stockholders or Wall Street.

There are “Blues” in every state, all of which started decades ago as nonprofits. But many have since made the switch to for-profit, allowing them more varied access to capital markets and the leeway to make more risky investments. There are fewer restrictions on their activity.

Nonprofits are expected to invest money in ways that have a clear benefit for their members, and in North Carolina, lawmakers have placed additional limitations into statute. For example, Blue Cross NC is not allowed to spend more than 10% of its reserves at any given time.

Blue Cross NC has argued this slows the company down in a fast-paced business environment; Obusek countered that the company has “been able to do most of what they’ve wanted to do. We haven't stood in their way.”

Within the current regulatory framework, Blue Cross NC has certainly thrived. It has the largest market share of any insurer in the state, and as Commissioner Causey told Lambeth’s committee in March, the company covers around 83% of the individual market and nearly 80% of the group health insurance market.

More than 2.3 million North Carolinians get their insurance directly from Blue Cross NC, and about 2 million more are part of private-employer-sponsored plans that have hired Blue Cross NC to administer them. Half a million Medicaid recipients have Blue Cross NC as the managed care organization administering their benefits, and Blue Cross NC also administers Medicare Advantage and Medicare Supplement plans for many seniors.

But competition is getting stiffer. Blue Cross NC is about to lose a notable chunk of that business after State Treasurer Dale Folwell announced in January that Blue Cross NC will no longer be the administrator of the State Health Plan starting in 2025.

The three-year contract to administer coverage for the 750,000 state employees and families it covers will instead go to Aetna, one of those big-and-getting-bigger national for-profit insurers with which Blue Cross NC says it must compete.

A changing insurance industry

Before the Affordable Care Act, insurance companies had more ways to make money. They could charge more if someone was older, if they could possibly get pregnant, or if they had a preexisting condition. They could also deny coverage to people with preexisting conditions—which meant they’d spend less money on expensive medical bills.

The ACA also dictated that insurers must spend at least 80% of what they receive from premium holders on patient medical care. This “medical loss ratio” left 20% of revenue from premiums for things like overhead, patient services, marketing and executive compensation. For a while, this curbed the profits to be made from their insurance business.

Many insurers readjusted within a few years, and learned how to game the medical loss ratio by arguing—sometimes legitimately—that things like the cost of the 24-hour nurse helplines, some advertising, and other services were part of patient care.

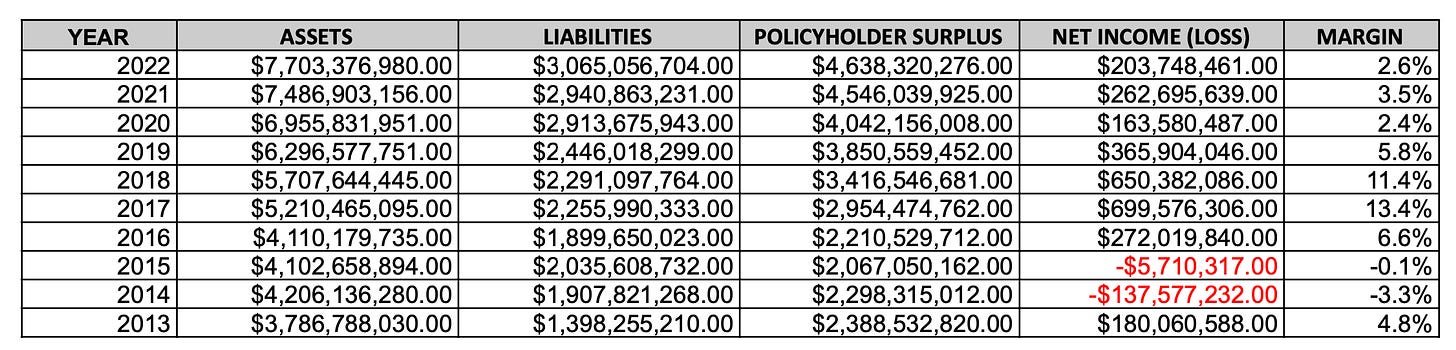

Blue Cross NC lost money in 2014 and 2015 but has been profitable ever since, including during the pandemic. In the past decade, the company accumulated so much reserve cash that it had to pay rebates to policyholders due the ACA cap.

If Blue Cross NC succeeds in getting permission to create a new holding company, it could move excess reserves into it and avoid triggering the ACA’s rebate requirement, Obusek said.

Source: N.C. Department of Insurance

“One of my biggest concerns is making sure there's some mechanism to get money back in the hands of policy owners,” Obusek said. “If somebody is hugely successful, then some of that somehow should come back and get back to North Carolina policyholders.”

‘The new arms race in health care’

All the changes to federal policy have prompted insurers to find new ways of making money.

Larger national players like Aetna, UnitedHealthcare, and Cigna—all for-profit companies—have grown by extending their insurance footprints and by buying up everything in sight, including physician practices, pharmaceutical distributors, home health agencies, and other health care companies. It has also led to megamergers. CVS, the pharmacy company, acquired Aetna, while UnitedHealthcare acquired OptumRx, a pharmacy benefits company.

For UnitedHealthcare, the strategy has paid off in record quarterly profits. Its pharmacy benefits business has consistently had a higher profit margin than its traditional insurance operation.

These purchases have been part of a strategy of “vertical integration”—basically, the health care insurer also becomes the health care provider. As a patient, you might get your insurance from Aetna, which then directs you to its parent company CVS to get your medications. If you need home health, you might get directed to another affiliate.

More recently, insurers have also started to acquire provider groups, which effectively eliminates the divide between the payer (an insurance company) and the prescriber (your doctor).

The effect is that more policyholders’ dollars stay in-house. It’s happening across the insurance industry, which could have consequences for Blue Cross NC’s business.

“The traditional payer-provider dynamic is being challenged,” Blue Cross NC wrote in its 2022 annual report. “As providers continue to consolidate and integrate physician groups and hospitals, we may experience upward pressure on reimbursement amounts.”

It’s an open question whether consolidation, which hospital systems and private equity firms are also driving, is good for patients. Christopher Whaley, a health economist with the RAND Corporation, called the trend the “new arms race in health care.” All the players are competing to snap up assets.

He said it’s potentially a good thing for patients because it creates incentives for doctors to coordinate care.

“If you employ physicians, you control the routes by which patients navigate the health care system, and so physicians and primary care physicians determine referral networks where patients go for specialty care, and how patients access hospitals,” Whaley explained. “Rather than, say, going out and acquiring a really expensive hospital, if you’re—maybe to use their term—‘nimble’ and go acquire a physician practice, then you can end up with the same results and spend millions instead of billions.”

Some suspect that is Blue Cross NC’s ultimate plan. But its chief financial officer, Mitch Perry, pushed back on the premise.

“Our approach with providers is very much a collaborative approach,” he said, detailing investments the company has made in mental health, in creating apps to help people through their pregnancies and in efforts to support the back office capabilities of independent practices. “For us, it’s more about partnership. It’s more about how we support and work with providers.”

Skeptics at the legislature have been harder to convince.

“They’ll never convince me that [Blue Cross NC executives] aren’t somewhere in the back room thinking about ‘where do we go with a changing landscape in health care and where do we position ourselves in the future?’” Lambeth said. “I think they’ve got to be thinking about what other big health systems, health plans are doing.”

That skepticism is bipartisan.

“While our office understands that Blue Cross Blue Shield operates in a competitive landscape, we continue to be concerned about how this legislation might impact its customers and the public’s investment in the company,” wrote Democratic Attorney General Josh Stein in an emailed statement. “We look forward to continued conversations to find the right balance.”

Perhaps the most consequential skeptic has been Causey, the insurance commissioner, who told Lambeth’s committee that HB 346 “is not a good bill in its current form. And I believe it will hurt the people in North Carolina, and that’s my job is to protect the consumers.”

“North Carolina consumers could benefit from more competition, and I think we need more competition,” Causey said. “But Blue Cross claims that this reorganization is necessary because it is now limited on how it can invest in other companies, by existing statutes that do not apply to for-profit insurers.”

He said that Blue Cross NC should not be able to invest with the freedom of a for-profit company, because nonprofit insurers are fundamentally different.

“For-profit companies make investments using stockholder money,” he said. As a nonprofit, “any Blue Cross NC money they’re seeking to invest, this is North Carolina policyholder money.”

Causey has also taken the company to task for using that money to pay six-figure bonuses to executives.

“If they’re paying million-dollar bonuses to executives every year, they pay $6 million to the CEO when we’re looking, what can they do when we’re not looking?” he said at his press conference this week.

A spokesperson for Causey confirmed the department has been working with the company on a set of changes to the bill that are expected to be introduced in the House during a hearing on Tuesday morning.

Passing this legislation is the top priority for the powerful lobbying operation at Blue Cross NC. The company’s political action committee made about $277,000 in campaign donations to state candidates in the 2022 cycle, and it has other ways of exerting influence.

For example, the company is behind advocacy campaigns like the Affordable Healthcare Coalition of North Carolina, a purportedly grassroots campaign with a host of Blue Cross NC connections that touts its own political action committee and accompanying public scorecard grading lawmakers based on certain key health policy votes.

Most lawmakers who’ve signed on as co-sponsors received A’s and B’s. Lambeth—who despite shepherding Medicaid expansion legislation for the last eight years—got an F, which he said made him laugh.

“I’ve not had the best of relations with Blue Cross, because they don't like some of the things that I advocate for,” Lambeth said.

Blue Cross NC employed 11 lobbyists last year, paying $557,964 to contract lobbyists, on top of their staffers. The 14 they have this session includes former Republican House Speaker Harold Brubaker and his son; Becki Gray, formerly of the John Locke Foundation; and LT McCrimmon, Gov. Roy Cooper’s former legislative liaison. Round a corner in the legislative complex and you’re likely to run into a Blue Cross NC lobbyist engaged in a conversation with a lawmaker.

Converting taxpayer benefit

For skeptics, one of the most important questions is how a new structure would make use of the assets Blue Cross NC has accrued over its years as a non-profit.

Peter Kolbe served as lead counsel for the state Department of Insurance in the 1990s, when the legislation that currently regulates the company was written. He explained that legal doctrine requires institutions to “give the assets you have developed as a result of being a nonprofit, including the tax breaks you had, back.”

The best example, he said, would be creating a charitable foundation that addresses health care needs within the state. Such a foundation was recently created in western North Carolina when the nonprofit Mission Health system was sold to the for-profit company HCA for $1.5 billion. Mission directed nearly two-thirds of the funds to the creation of the Dogwood Health Trust. A similar nonprofit conversion foundation was formed after Novant purchased New Hanover Regional Hospital in 2020.

Consumer advocates argue that if Blue Cross NC gets what it wants, they should do right by the taxpayers who supported the company for all those years.

That’s played out in other states. When California’s Blue Cross became the for-profit Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield in May 1996, it endowed the California Health Care Foundation and the California Endowment with $3.2 billion. Blue Cross insurers in Montana, Michigan, New York, and other states have made similar conversions, though fights have ensued over the size of the eventual endowments.

A proposed organizational chart that Blue Cross NC lobbyists have been handing out at the General Assembly.

Blue Cross NC says it's not interested in converting its insurance entity to a for-profit. And if the bill passes, it likely wouldn’t need to. The reserves from the insurance division could be moved into the holding company, which could then buy subsidiaries and make investments like any other for-profit business.

“This holding company would not have any regulatory oversight, not by the department, or the insurance commissioner, or anybody else,” Obusek said. “There’s no regulatory oversight at present, in the bill as drafted, for that holding company.”

That frustrates consumer advocates, many of whom watched a very similar fight play out in the late 1990s when Blue Cross NC did want to convert its insurance business from nonprofit to for-profit. At that time, the legislature created a study commission.

Out of that yearlong effort came statutes that would require Blue Cross NC do what has been done in California and other states—create a foundation to serve the needs of the people who paid their premiums for 90 years.

The value of such a foundation, the statute said, would be “equal to 100 percent (100%) of the fair market value of the corporation.”

Blue Cross NC CFO Perry puts the company’s “statutory capital” at around $4.7 billion, money that could potentially move to the holding company. But he said he couldn’t quote an estimate of what the fair market value of the company might be.

“It’s something that we don't track and aren’t looking at,” he said. “It hasn't been meaningful to us and isn't meaningful to us, because we're focused on our customers, we're not focused on what it would be to have shareholders.”

Needless to say, it would be large, and such a foundation would grant game-changing sums, particularly for rural parts of the state.

The last section of the bill currently under debate would give Blue Cross NC the ability to instead create a foundation from the assets of just the holding company—the value of which could be diminished under the new organizational structure.

Kolbe, who was lead legal counsel for the Department of Insurance in the 1990s when the original study commission was active, said that provision “has the potential to reduce the assets of the Blue plan such that in any conversion that were to occur, there are fewer assets to place.”

Kolbe said that one change that could assuage concerns would be amending the language to say the value of any conversion foundation should include the fair market value of the nonprofit holding corporation “and all of its subsidiaries.”

Who stands To gain

For North Carolinians, what matters is simple: Will these changes lead to lower prices and better care?

While Whaley, the health economist, sees the potential for vertical integration to benefit consumers, he also acknowledged that it will give insurers a way to skirt Affordable Care Act restrictions. If you own both the insurer and the provider, you can “pay yourself a lot.”

“Whether that's happening or not, we don’t [yet] have good data,” he said. "But that is a potential concern.”

Barak Richman, a Duke Law School professor who’s usually critical of health care consolidation, is holding off on making a judgment.

"If they can use a holding company to buy other things—you know, I can see the concern with that,” he said. “But I can also see how, in this particular health care marketplace, we really want an insurer that can play with a full deck."

Richman said that if given a choice between having hospitals or insurers buy up physician practices, he’d take the insurers. The data are clear that when a hospital buys a physician practice, prices only go one way: up.

But he also said that either of those choices is better than private equity companies getting into the game, as they have started to do.

The best thing, Richman said, is for independent physicians to stay that way, something Blue Cross NC says is their intent.

“Something that is core to what we're what we're trying to do ... is helping physicians stay independent,” Perry said. “This is what we're doing with supporting urgent care. It's what we're doing with investments in helping independent physicians take risks in different ways.”

He said that their goal is for providers to feel like they don’t have to seek hospital or private equity acquisition to keep their practices afloat.

Johns Hopkins researcher Ge Bai said that Blue Cross NC, hospitals, other providers, and insurers are simply responding to the incentives baked into a health care system built on third-party payment.

“This system compels power consolidation on both sides,” she said. “Payers have to consolidate so they can negotiate a better price and then providers must consolidate to counter, so it's really a back-and-forth game.”

Bai has worked with state Treasurer Folwell to look at what state hospitals are charging and the power they have to drive insurance prices as a result.

“The provider is so powerful,” Bai said, while insurers “cannot do much.” What consolidation means for policyholders just isn’t yet clear.

It’s one of many things that’s still uncertain, along with the full intent of the legislation, what the company actually wants to do, and why Blue Cross NC has made such an urgent push. Bradford, the bill’s lead sponsor, has been an enthusiastic public supporter for Blue Cross NC. Last week, he made his plans official to run for state treasurer, a role that would help determine whether Blue Cross NC regains its role over the state health care plan when it renews.

Blue Cross NC’s strong bipartisan support among legislators—evidenced by the ranks of cosponsors in the Senate and House—could lead to swift passage if some compromise is reached.

From the outside, one thing is clear: There are many who want this effort to slow down and be more transparent.

“The legislature has to do more than just listen to Blue Cross lobbyists,” Richman said. “I mean, have there been any hearings? Has there been any studies that have been commissioned? We have, I always like to think, some world-class health care scholars in the state. I don't think that any of them have been called."

Rose Hoban is the founder and editor of NC Health News. This story was reported and edited through a partnership among The Assembly, NC Health News, and The Charlotte Ledger.

Need to sign up for this e-newsletter? We offer a free version, as well as paid memberships for full access to all 4 of our local newsletters:

➡️ Opt in or out of different newsletters on your “My Account” page.

➡️ Learn more about The Charlotte Ledger

The Charlotte Ledger is a locally owned media company that delivers smart and essential news through e-newsletters and on a website. We strive for fairness and accuracy and will correct all known errors. The content reflects the independent editorial judgment of The Charlotte Ledger. Any advertising, paid marketing, or sponsored content will be clearly labeled.

Like what we are doing? Feel free to forward this along and to tell a friend.

Social media: On Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn.

Sponsorship information/customer service: email support@cltledger.com.

Executive editor: Tony Mecia; Managing editor: Cristina Bolling; Staff writer: Lindsey Banks; Contributing editor: Tim Whitmire, CXN Advisory; Contributing photographer/videographer: Kevin Young, The 5 and 2 Project