How tied are Charlotte leaders’ hands on spending tourism tax money?

Charlotte and Asheville have two very different approaches to spending the tourism taxes they collect.

You’re reading Transit Time, a weekly newsletter for Charlotte people who leave the house. Cars, buses, light rail, bikes, scooters … if you use it to get around the city, we write about it. Transit Time is produced in partnership between The Charlotte Ledger and WFAE.

As Charlotte pumps tourism money into sports stadiums, Asheville is spending it on greenways and parks — and now maybe affordable housing and transit, too

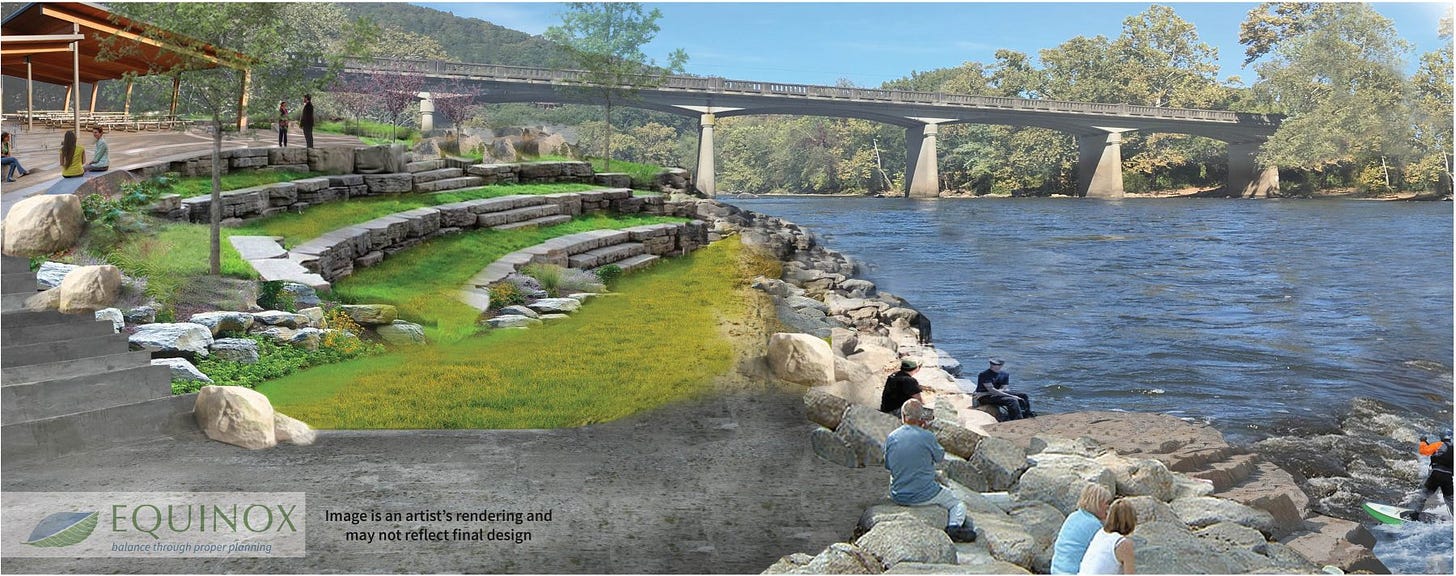

The Woodfin Blueway and Greenway, which includes five miles of greenway trails and parks along the French Broad River north of Asheville, received $8.1 million in tourism taxes collected from the Asheville area. Leaders in Asheville routinely spend tourism tax money on greenways and parks, which is something Charlotte doesn’t do. (Rendering courtesy of RiverLink)

By Tony Mecia

When the city of Charlotte agreed to put $215 million into upgrading the Spectrum Center, the home of the Charlotte Hornets, it drew on a pot of money collected from taxes on hotel rooms and dining out.

When the city upgraded Bank of America Stadium in 2013 at a cost of $88 million, it drew on that same pot of money, which local leaders refer to as tourism taxes. That money is expected to play a prominent role in upcoming stadium renovations, too, which could come with a price tag to the city of $600 million or more.

And when the city last summer had a chance to land a major tennis tournament, the Western & Southern Open, by helping build a tennis complex in the River District development on Charlotte’s westside, it quickly was able to scare up a commitment of $65 million from — you guessed it — those tourism taxes. (The tournament ultimately stayed in Cincinnati.)

Part of Charlotte’s justification for committing large sums to pro sports facilities is that tourism tax money must be spent on tourism projects. City leaders have said repeatedly that under state law, as much as they might like to, they just cannot spend that bucket of tax money on other pressing city priorities such as transit, police and affordable housing.

Yet leaders in Asheville have found a way to use tourism taxes collected in their community to pay for many of those very same priorities. For years, tourism funds in the Asheville area have gone toward building greenways. And now, after a change in state law, some of that money could flow toward supporting affordable housing in Asheville, and maybe transit, too.

How Asheville did it: Asheville accomplished that goal of using tourism tax money for a wider set of projects in a few different ways. First, leaders there have taken a more expansive view than Charlotte of what constitutes expenditures that are “tourism-related.” And second, business and political leaders in Asheville reached a consensus and developed the political will to change the law to distribute the benefits of tourism money more broadly, while Charlotte leaders generally refer to tourism taxes as by and for the benefit of the local hospitality industry.

It’s true that Charlotte and Asheville are different, of course: Asheville’s economy is more dependent on tourism than Charlotte’s, which means that more of its everyday activities could be more heavily tourism-related. And it lacks the major pro sports teams that bring national attention and millions of dollars in economic development. (Asheville does have a single-A baseball team, the Asheville Tourists, whose century-old ballpark received a commitment of $23 million in tourism money last year.)

Asheville Mayor Esther Manheimer, in an interview with Transit Time, says she thinks local governments in North Carolina have flexibility to interpret the restrictions on how they spend tourism taxes.

“To me, they are like the Bible — you can read them to mean whatever you want,” says Manheimer, who is a lawyer.

Unlike most state laws, the laws on raising and spending tourism taxes vary county-by-county. The law on that topic for Buncombe County, where Asheville is located, is different than it is for Mecklenburg County, for instance.

In Mecklenburg, the law says money goes toward the Charlotte Convention Center, with Charlotte and Mecklenburg’s towns splitting the balance using a complex formula. The Charlotte Regional Visitors Alliance runs the convention center and other city entertainment complexes, and promotes tourism, using a portion of the money. The City Council also spends tourism tax money on sports stadiums, cultural facilities and other uses, including a pledge last year for $30 million toward redeveloping the old Eastland Mall site into an indoor sports complex. The law allows spending tourism taxes in Mecklenburg only on “tourism and tourism-related programs and activities.”

The 8% tax on hotel rooms and the 1% tax on prepared food collected in Mecklenburg totaled $74.3 million in 2021-22, according to the N.C. Department of Revenue, the most recent year available. [edited 4/8/24 to correct tax on hotel rooms]

In Buncombe County, the law gives control of the hotel tax money to a Tourism Development Authority. (The county doesn’t have a prepared food tax.) Until 2022, the law directed the authority to spend 75% of the money to promote tourism and the rest on projects that “significantly increase patronage of lodging facilities in Buncombe County.”

In the last decade, that language has been interpreted to allow spending on parks, soccer fields, greenways, farmers markets, art centers and museums — a total of $80 million on 40 “community projects,” according to the Buncombe County Tourism Development Authority. Some of the projects paid for in part by tourism money in Buncombe County include:

$2.3 million for the first phase of the Swannanoa River Greenway, a 1.3-mile stretch that expands the greenway network to Asheville’s east side and was a top priority in the city’s greenway plan.

$8.1 million for the Woodfin Blueway and Greenway, which includes five miles of greenway trails and parks along the French Broad River.

$10.8 million on the Enka Recreation Destination, a sports park that includes a greenway, pavilions and a dog park.

Asheville draws many tourists, and building greenways to connect different parts of the area is seen as an amenity that promotes tourism, Manheimer said.

“Greenways have never been controversial here,” she says. “That has always been allowed.”

The Swannanoa River Greenway received $2.3 million in tourism tax money in 2022. It is one of Asheville’s top greenway priorities. (Courtesy of city of Asheville)

Lisa Raleigh, executive director of RiverLink, a nonprofit that is helping develop the Woodfin Blueway and Greenway project, said via email that Buncombe County’s Tourism Development Authority was a “key supporter” of the project. “We are extremely grateful for their belief and investment,” she says.

In contrast, political leaders in Charlotte don’t spend tourism tax money on greenways. The funding for the local greenway system here comes primarily from Mecklenburg County property taxes and bonds. The federal government has also helped fund some sections, and the city of Charlotte is building the $113 million Cross Charlotte Trail using a mix of money from bonds, property taxes and cost savings from other projects. Charlotte’s Housing Trust Fund to subsidize affordable developments is also funded by city-issued bonds.

‘People had just had it’

In Asheville, some leaders wanted tourism tax money to do even more, after becoming concerned that too much money was being spent to promote tourism and not enough on community needs.

“People had just had it,” Manheimer says. “Us politicians had had it, too. We had so many projects that we needed funded that we didn’t have enough resources for.”

So political and business leaders worked with Republicans in the General Assembly to alter the law on how tourism tax money from Buncombe County could be spent. Changes to the law in 2022 cut the portion spent on promoting tourism from 3/4 to 2/3 and directed that the increased money on projects both increase tourism and “benefit the community at large in Buncombe County.”

Manheimer says the effort succeeded only through a “complete consensus” among hotel owners, tourism leaders and elected officials.

“We just had to get all the people that the legislature would listen to to be in agreement with it and push it,” she says.

At the time that the bill was passed, according to the Asheville Citizen-Times, Republican Sen. Chuck Edwards, who represented a portion of Buncombe, praised local hospitality leaders for their “keen and unselfish interest in investing more of the tax proceeds generated by their industry to benefit Buncombe County residents.”

Defining affordable housing and transit as ‘tourism-related’

The county’s Tourism Development Authority is now in the middle of its first funding cycle under the new rules for using tourism tax money. County leaders said in November that they were seeking $6 million from the tourism fund to help pay for a planned 600+-unit mix of single-family houses and apartments that includes affordable housing, greenways and small parks. The theory is that the homes would be available to tourism-industry workers, thereby meeting the goal of supporting tourism.

In Mecklenburg, political and business leaders also sought changes in how to spend tourism tax money: They pushed to extend the 1% tax on prepared food by 30 years, a move generally seen as a way to secure more funding for eventual renovations to Bank of America Stadium.

Local political leaders of both parties in the Charlotte area have depicted tourism taxes as taxes that the local hospitality industry chooses to levy on itself, for the benefit of that industry — though residents who live here pay them, too, when they go out to eat.

“I consider this a tax that’s really for the hospitality industry,” Charlotte Mayor Vi Lyles, a Democrat, said during a May appearance on WFAE’s “Charlotte Talks with Mike Collins.”

Republican Rep. John Bradford of Mecklenburg County, who helped win passage of the measure in Raleigh, told The Charlotte Observer in May: “Leaders in the hospitality industry came to me with the need to extend the financial tools that have created tremendous growth throughout the Charlotte region and allow our hoteliers, restaurateurs, and businesses in the region to continue with their success.”

The Charlotte Hornets last week released details of planned upgrades to the Spectrum Center, paid for with $215 million from tourism taxes approved by the City Council last year. Changes include renovations to hospitality suites and clubs (left) and the addition of 2,500 seats in the lower level of the arena (right). The Hornets said the team is unsure how much it is committing to the project “as we work through the full scope and final costs,” a spokesman said. The renovations are scheduled to be completed in 2025. (Courtesy of the Charlotte Hornets)

Manheimer says that Asheville’s experience shows that business and political leaders working together can help fund community needs with tourism tax money. There’s even been talk lately, she says, about whether tourism taxes might be used to help pay for transit around Asheville, on the theory that the tourism sector needs workers who can reliably show up to their jobs.

She says: “The trepidation is that once you start funding affordable housing and transit with the room tax, with this premise that supporting working in the tourism economy supports tourism, you can pretty much argue anything.”

Tony Mecia is executive editor of The Charlotte Ledger. Reach him at tony@cltledger.com.

Transit Time is a production of The Charlotte Ledger and WFAE. You can adjust your newsletter preferences on the ‘My Account’ page.

Did somebody forward you this newsletter and you need to sign up? You can do that here:

Other affiliated Charlotte newsletters and podcasts that might interest you:

The Charlotte Ledger Business Newsletter, Ways of Life newsletter (obituaries) and Fútbol Friday (Charlotte FC), available from The Charlotte Ledger.

The Inside Politics newsletter, available from WFAE.

Great article, thanks for researching and writing this. With Charlotte having high tourism density in uptown and heavy auto-centric traffic in and out of the center city, funding transit, greenway recreational facilities and affordable housing for hospitality workers all make a lot of sense. Thinking of mass transit and greenways as commuter alternatives to more cars on the road could help quality of life for all residents.