So what’s a 'mobility hub,' anyway?

Buses, scooters, bikes and more — all in one spot

You’re reading Transit Time, a weekly newsletter for Charlotte people who leave the house. Cars, buses, light rail, bikes, scooters … if you use it to get around the city, we write about it. Transit Time is produced in partnership between The Charlotte Ledger and WFAE.

Charlotte envisions about 100 ‘mobility hubs’ throughout the city to encourage using different forms of transportation

A possible “mobility hub bus bay” could make using transit easier and more inviting. (Courtesy of Charlotte Area Transit System)

By Ely Portillo

WFAE

If you follow transit news with any regularity, you’re used to the jargon: CATS, CRTPO, MTC, headways, first mile/last mile, revenue passenger service, etc. And if you follow Charlotte’s transit plans, you’ve probably heard one of the newer terms: mobility hubs.

Local transit planners have talked up mobility hubs for the past few years. They’re a key part of Charlotte’s vision for a comprehensive transit system that’s able to lure people out of their cars and onto buses and trains. But it still feels kind of hard to pin down what exactly … they are.

“We are very guilty in the planning world, and in the technical space, of throwing out words and expecting people to pick up on it,” said Jason Lawrence, the Charlotte Area Transit System’s chief planning officer. Even visual depictions of a new concept like “mobility hubs” can end up looking like “an image salad,” Lawrence said.

So we’ve decided to devote our main story in this Transit Time newsletter to the simple question: What is a mobility hub?

At its simplest, a mobility hub is just a fancier (or more jargon-y) bus, train or streetcar stop that combines several different modes of transportation in the same place

“Essentially what a mobility hub is, is a bus stop, a park and ride, a light rail station — it is just creating space for other types of mobility and building space for them there,” Lawrence said. “A bus stop of the past, you could do one thing, and that's pick up passengers.”

Picture a bus stop that also includes a bike rack and a drop-off or pick-up area set aside for Uber. Or a light rail station that also includes bus bays, a parking garage and a covered area for an electric shuttle taking riders to a nearby office park.

Mobility hubs, which the city of Charlotte hopes to expand in the coming years, are places where different means of transportation come together. (Source: Charlotte Strategic Mobility Plan)

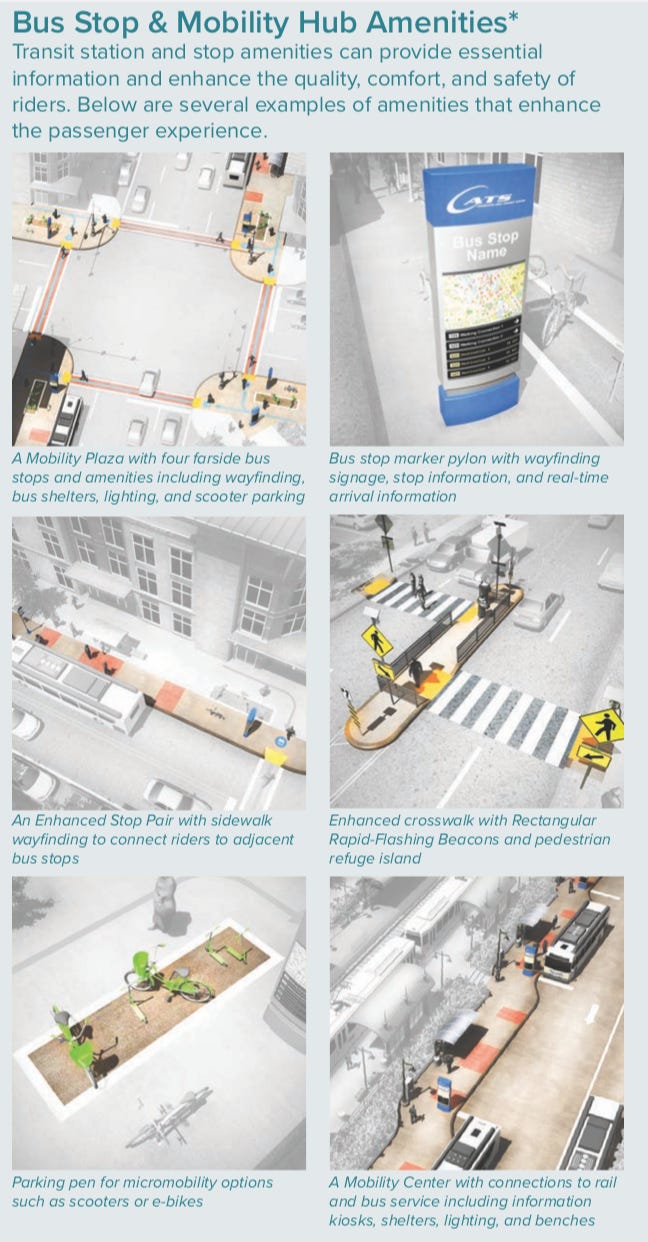

Charlotte’s plans call for three basic levels of mobility hubs (more details are in Appendix D of the Envision My Ride bus system plan):

The most basic would be enhancements to the city’s existing bus stops. These could include secured parking for bicycles, or a place for a shuttle taking people to and from nearby destinations. “Really basic stuff,” Lawrence said.

The next level up would be at locations where two bus lines cross. These are often unmarked, or minimally indicated by signs, and don’t feel like formal locations where riders can transfer from one line to another. Enhancing these stops to make them feel like real “transfer points” would include adding shelters for riders to wait, lighting, schedule information and parking. “It’s taking that intersection and making transfers more seamless,” Lawrence said.

The third and most elaborate would be “mobility centers.” These are light rail stations, park-and-ride locations, and transit centers like uptown’s main bus station and the old Eastland Mall site, where many lines intersect. These enhanced centers would also include parking, bus bays, paratransit, space for ride share, bike storage and charging for electric vehicles. Lawrence said the exact mix of amenities and transportation options at each would vary based on the surrounding context. Suburban park-and-rides could probably accommodate more than an urban streetcar station, for example.

So, it’s not exactly rocket science — just combining more modes of transportation into the same location. But Lawrence said that’s an important mindset shift if planners hope to reach Charlotte’s long-term goal of getting people to take 50% of all trips in something besides a single-occupancy vehicle.

“If we're going to achieve that goal, we've really got to make it easier and simpler to use transit and all forms of mobility,” he said. “The ability to make it easier to use them is how we get there. We have to create these smaller hubs throughout the system to make it happen.”

And, Lawrence said, it’s important to make it easier for people to use transit by bringing more modes of transportation into transit stops (with, say, designated places for ride-hailing companies to drop people off at all light rail locations).

“It's an acknowledgment that the mobility ecosystem is much larger than just transit,” he said. “We need to integrate all types of mobility into our transit system…A 40-foot bus can’t solve every single need.”

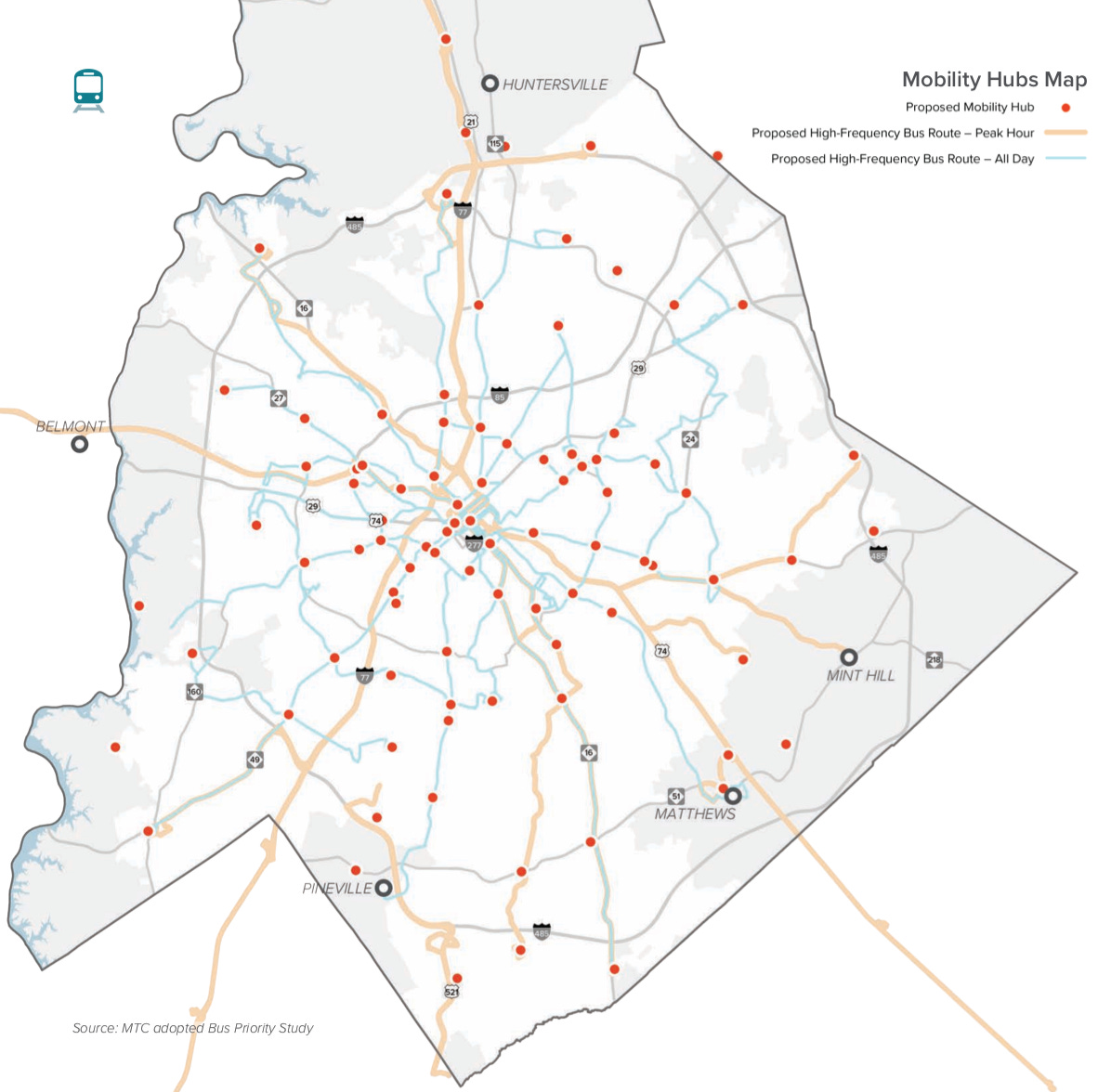

Mobility hubs, marked here by red dots, could range from enhanced bus stops to full-blown “mobility centers” with many options such as bike storage, electric vehicle charging and parking. (Source: Charlotte Strategic Mobility Plan)

There’s one more big question: With about 3,000 bus stops, how will CATS pay for its new mobility hubs? First, only 93 locations are recommended for the two more elaborate levels of mobility hubs.

And Lawrence said they won’t all be built at once. Funding would come from a number of sources: the regular capital budget, a new 1-cent sales tax (if, one day, that makes it to the ballot and voters approve), and working with developers. He pointed to the Ballantyne Reimagined development, which has space reserved for future transit stops, as an example of the latter (the River District is another).

Also, it’s not all about building new mobility hubs. It’s partly a question of branding, Lawrence said. The system already has 26 light rail stations, 17 streetcar stations, four bus transit centers and six park-and-rides. Many of them already include some or all of what CATS is seeking to build with its mobility hubs and centers, like bus bays and bike parking, but don’t necessarily emphasize (or market) those things, and make them easy and comfortable for riders to use.

“In some ways, we have these locations already in place,” he said. “It’s taking fuller advantage of them.”

Ely Portillo is senior editor for news and planning at WFAE, Charlotte’s NPR news source. He was previously with the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute and spent a decade as a reporter at The Charlotte Observer. Reach him at eportillo@wfae.org

In brief…

Gold Line lawsuit rumbles on: A lawsuit against the city of Charlotte by the contractor who extended the Gold Line streetcar will go to trial in March 2025 at the earliest. Johnson Bros. Corp. says the city breached its contract and that it is owed more than $100 million, after the two sides squabbled over who was responsible for construction delays. (Charlotte Business Journal, subscriber-only)

CATS schedule changes: The Charlotte Area Transit System adjusted some of its bus routes this to improve on-time reliability. (WCCB)

Transit Time is a production of The Charlotte Ledger and WFAE. You can adjust your newsletter preferences on the ‘My Account’ page.

Did somebody forward you this newsletter and you need to sign up? You can do that here:

Other affiliated Charlotte newsletters and podcasts that might interest you:

The Charlotte Ledger Business Newsletter, Ways of Life newsletter (obituaries) and Fútbol Friday (Charlotte FC), available from The Charlotte Ledger.

The Inside Politics newsletter, available from WFAE.