You’re reading Transit Time, a weekly newsletter for Charlotte people who leave the house. Cars, buses, light rail, bikes, scooters … if you use it to get around the city, we write about it. Transit Time is produced in partnership among The Charlotte Ledger, WFAE and the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute.

Editor’s note: This article was published earlier this week by The Food Section, a twice-weekly newsletter covering food and drink across the American South. It is republished with permission. The Food Section is an independent, journalist-run publication that reports on stories not pitched by publicists. You can find out more about The Food Section here, and Ledger readers can subscribe at a 25% discount.

Vehicles slam into restaurants, causing 18 deaths across the South since 2016; experts debate how to guard against ‘pedal error’

Four people were hospitalized after a car smashed into a Chipotle in Woodbridge, Va. (Photo by Prince William County Department of Fire and Rescue)

by Hanna Raskin

Cecil Patterson, the third speaker at the Aug. 20 joint funeral of Christopher and Clay Ruffin, seemed like an unlikely person to eulogize the brothers.

Patterson didn’t drive buses with Chris, 58, at Fike High School, or dote on the 62-year-old Clay’s little granddaughter the way that her proud Papa did. As a white man in a short-sleeved salmon button-down shirt, Patterson stood out at L.N. Forbes Original Free Will Baptist Tabernacle, a predominantly Black church in the town of Wilson, east of Raleigh.

But as he haltingly explained to the assembled mourners, “Sunday morning, I was at Hardee’s when it happened. … Everybody in there crying and carrying on. I guess I was probably the last person…”

The Ruffins were having breakfast at Hardee’s on Aug. 14 when a 78-year-old man leaving a nearby car wash lost control of his Lincoln Aviator, smashing into the plate glass window alongside the Ruffins’ table with so much force that glass shards showered the front counter. The scene was horrific, with a 7-year-old boy trapped beneath the SUV and limbs severed by the impact.

“We need help and help bad,” a 911 caller from the restaurant told a dispatcher.

Deadly car crashes inside buildings represent a tiny fraction of traffic fatalities. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 13 people were killed by cars while in or on a building in 2020, just above the annual average for such incidents. By contrast, the agency recorded 38,824 total traffic fatalities that year.

Yet safety advocates are concerned about how frequently cars have been striking buildings, particularly as the population of elderly drivers edges upward and the overall number of fatal crashes has surged nationwide. Data from the Storefront Safety Council shows commercial buildings are hit by cars 100 times a day, on average, with restaurants accounting for roughly one-quarter of those incidents.

Many of those collisions are soft taps that amount to nothing more than insurance headaches. But at fast-service restaurants, where parking spots are conveniently located close to the building and patrons tend to cluster by the windows, serious injuries can result when a driver plows into the dining room at high speed.

Just a day after the Ruffins were killed, a 70-year-old man in Raleigh mistook his Toyota’s gas pedal for his brake, wrecking the outdoor deck of Rudino’s Sports Corner.

The next day, a woman who thought she was backing out of This Is It! Southern Kitchen & Bar-B-Q in Riverdale, Ga., instead drove through the front door, sending one person to the hospital.

“It’s one thing if you’re in warfare and bombs are going off,” says Rob Reiter, co-founder of the Storefront Safety Council. “But if you’re sitting in a restaurant, the PTSD is usually because it’s so violent and unforeseen: You have your back to the street and the next thing you know, you’re 30 feet down with a table on top of you.”

A focus on crashes into buildings

Reiter chanced into the field of car crashes involving retail buildings after a career in high security, which involved mostly stateside assignments in the wake of 9/11.

“We started putting barriers in front of courthouses and NFL stadiums and all the places we thought Osama was going to drive a truck bomb into,” Reiter says, adding that he considered the efforts successful since “the only people driving into the barriers were drunks.”

Once Reiter started thinking about vehicles creating havoc in places where they don’t belong, he noticed the topic popping up in the news. After an 86-year-old man in 2003 confused his Buick’s accelerator with its brake, boring through a Santa Monica, California farmers market and killing 10 people, Reiter created a national incident database.

Two people were hospitalized after a car crashed into Sylvan Park Restaurant in Murfreesboro, Tenn. (Photo by Murfreesboro Police Department)

Between 2014 and 2022, his consulting firm documented more than 25,000 media reports of storefront crashes. The Storefront Safety Council defines a storefront crash broadly: For example, if a car nicked an Arby’s sign in the parking lot, or a truck spun into a former Ruby Tuesday, those incidents would merit entries in the neatly categorized spreadsheet.

A review of 523 incidents associated with restaurants in Southern states shows that there were 182 injurious car crashes inside Southern restaurants between Jan. 1, 2016, and the day of the Wilson, North Carolina, tragedy.

In more than half of those crashes, at least one of the injuries requiring medical attention was sustained by an employee or patron. Fifteen of the crashes caused one or more fatalities.

As Reiter likes to point out, restaurant workers and customers aren’t protected by airbags and thousands of pounds of steel. Some of the wrecks with injuries include:

Drink machines toppling on patrons, as happened to a woman at a Panda Express in Wilmington in 2020. A 78-year-old SUV driver dislodged the soda fountain when he slammed into the side of the restaurant, having mistaken the gas for the brake.

Gas lines rupturing. After a man in 2018 lost consciousness and drove his van into an Outback Steakhouse in Savannah, Ga., part of the ceiling collapsed and gas filled the kitchen, igniting flames that lashed six employees and the restaurant’s owner.

Broken bones, such as those experienced after a car rammed the table shared by 12 members of the Phipps family at La Bamba Mexican Restaurant in Greensboro last year.

‘Pedal error’ a recurring factor

Because Reiter’s database is based on preliminary reports, it’s impossible to draw conclusions about the leading cause of car crashes in restaurants across the region. In close to half of the injurious incidents, authorities were still trying to determine how a car ended up in the building.

In rare instances, that’s where the driver meant to put it.

For example, after an 80-year-old man in 2019 fought with another patron of 20’s Pub & Sub in Macon, Ga., he left the restaurant and then came back inside. Except this time, he was behind the wheel of a Chevy Colorado.

Other restaurant crashes are attributed to distracted driving. “The driver told investigators she was overwhelmed because her boyfriend broke up with her over the phone as she was driving,” an Atlanta TV station reported following an April crash into Brockett Pub House and Grill that destroyed an adjoining liquor store.

Alcohol and medical conditions also figure into injurious restaurant crashes, but the phrase that predominates the coverage is “pedal error.”

Douglas Young, a kinesiologist, has been studying pedal error since the 1980s.

“Drivers started to make claims about their vehicles running away and believing there was something that caused their car to accelerate even though they were pressing the brake,” Young says.

Young and a colleague reviewed North Carolina police reports from 1979 to 1995, looking for any evidence that vehicle defects were responsible for cars speeding up instead of stopping. The title of their study, published in 2010, is a total spoiler: “Cars Gone Wild: The Major Contributor to Unintended Acceleration in Automobiles is Pedal Error.”

In other words, drivers choose wrongly.

Changing designs of cars or parking lots?

According to Young, that makes the problem difficult to fix. He flatly rejects suggestions that pedal errors would decline if cars were designed differently. After all, “there is no design that can stop a driver if he or she puts a foot on the accelerator,” regardless of its shape, size or placement.

Reiter agrees that it makes little sense to try changing cars or the people controlling them.

“People have been trying to change driver behavior since they invented drivers, with very little success,” he says. “Look at seatbelts or cell phones.”

That’s why Reiter maintains the way to reduce restaurant crashes is to reconfigure parking lots.

First, Reiter would relocate accessible parking spaces. Never mind that putting disabled drivers at a greater distance from the restaurant door would violate federal law, or that the opinion is so frankly ableist that even Reiter admits he’s had trouble finding a sympathetic audience for it.

“If you go to your state’s DMV and you read what you need for an ADA tag, you’ll think people like that shouldn’t even be driving,” he says. “Congestive heart failure or neurological problems? Why would you aim that at a building? And why would you be surprised that if you aim something at a building, that something goes through the building?”

Second, and less controversially, Reiter would do away with nose-in parking. He reasons that if drivers pump the accelerator instead of the brake when they’re pointed toward the street, they stand to do less damage.

Finally, Reiter is a big fan of bollards. Harking back to the days when he set up barriers around potential terrorist targets, he wants restaurants to erect heavy-duty steel posts around their perimeters.

“It’s a cheap and easy solution,” he says. “If you just spend $600 to put in a bollard, you can save a life.”

Not everyone is so smitten with bollards.

“You can try, but you would have a world full of bollards and different accidents emerging with bicyclists or whatever,” Young says. “You can’t really design the environment to prevent these kinds of accidents.”

Nor does it appear that chain restaurants anxious to maximize profitability are in any rush to do so. Reiter is astounded that restaurants such as Applebee’s have introduced to-go parking spots, encouraging customers to idle their cars close to the kitchen and compose text messages announcing their arrival.

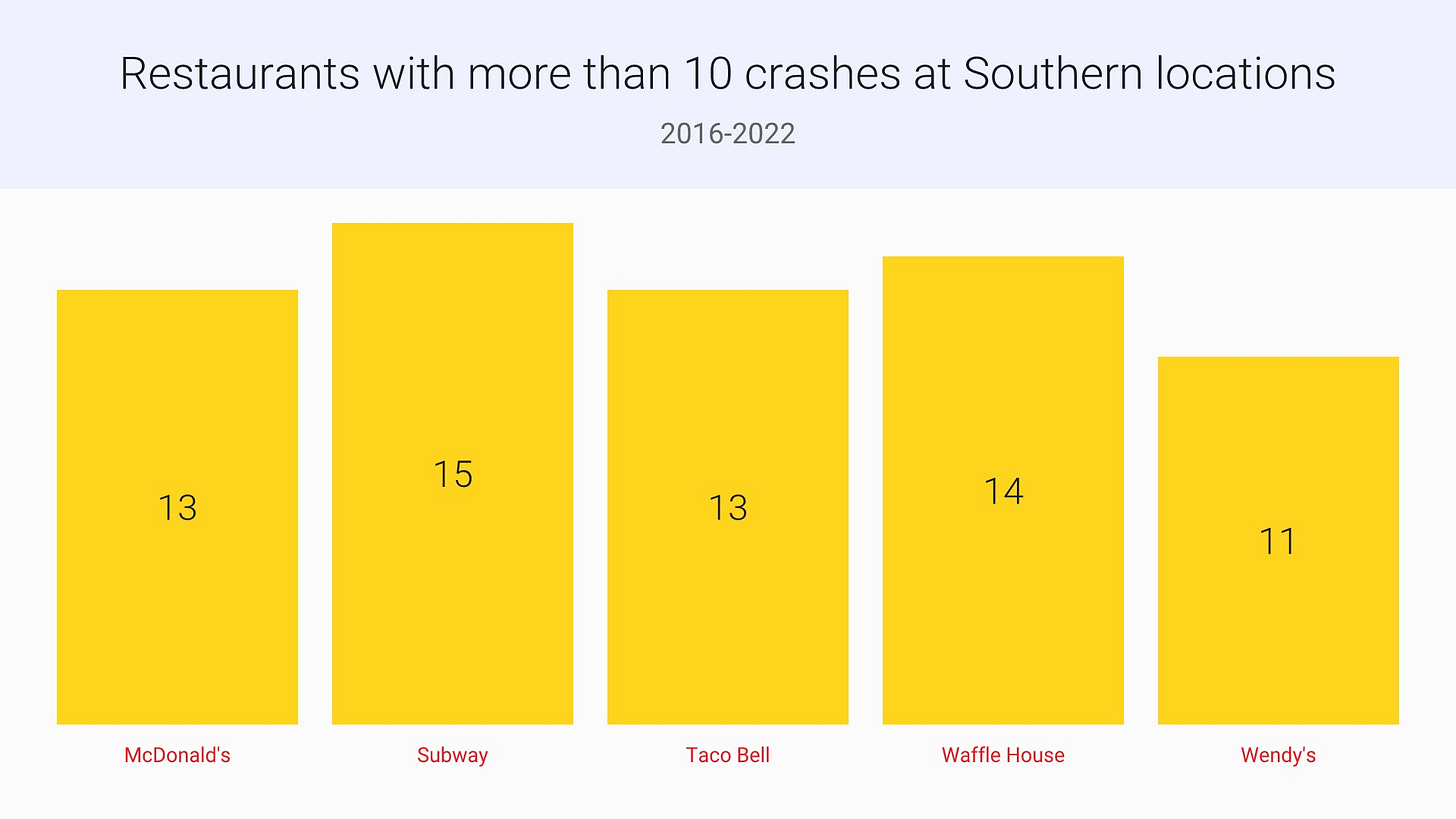

Representatives of McDonald’s, Subway, Taco Bell, Wendy’s, and Waffle House, which led the list of injurious crash sites in the South, did not return messages seeking comment.

“I can’t blame Hardee’s,” says Carolyn Etheridge, who was eating at the Wilson restaurant at the time of the fatal crash. Her car was totaled after one of the victims was ejected from the restaurant and went through it. “It wasn’t their fault. I think [the driver] tried to go across those five lanes of traffic and then when he did that, sure enough, he didn’t have enough time to brake.”

Traumatic memories

While the layout and ubiquity of fast-food restaurants means they’re more likely to be associated with multiple crashes, independent restaurants get hit by cars, too.

Johnson’s Drive-In in Siler City, south of Greensboro, was struck on Oct. 8, 2021. The driver of an SUV lost control of his vehicle, injuring three people and killing a 64-year-old pastor.

“You never think something is going to happen like this on your property to people who depend on you and trust you to feed them,” owner Carolyn Johnson Routh was quoted as saying at the time.

I was photographing one of Johnson’s famous cheeseburgers when Routh came outside to greet me. I explained that I was a reporter and wondered if she’d be willing to talk about her business being closed for months.

“It’s not PTSD or anything, but it’s very hard to talk about,” she said. “This sounds bad, but I try to put it out of my mind.”

When the SUV tore through the east wall of the brick building, Routh was sitting in that part of the restaurant.

She hasn’t gone back to that section since.

Hanna Raskin is a James Beard award-winning food writer in Charleston who founded The Food Section in September 2021. Her publication is currently a finalist in the Best Newsletter division of the International Association of Culinary Professionals and Online News Association’s awards contests.

In brief…

CATS plans on-demand service: The Charlotte Area Transit System plans to offer an Uber-like ride service in five areas of Charlotte starting next year: the University area, Hidden Valley, Camp North End, Pine Valley and Carolina Place area and the airport vicinity. A CATS planner said: “It’s a more flexible service that is appropriate for areas that can’t support … [a] 40-foot bus [with] 30-some-odd seats on it, whereas [with] microtransit, it’s a smaller vehicle. It’s more about right-sizing services to the ridership.” (Axios Charlotte)

City delays Saturday parking meter charges. The city of Charlotte is delaying a plan to start charging for weekend parking at metered spaces, which was supposed to go into effect last weekend. Charlotte had planned to start charging $1.50 an hour on Saturdays for metered spaces in uptown and South End. Instead, the spaces will remain free to use on Saturdays until “later next year.” The city is conducting “an overall review and action plan for on-street parking and curb space management.” (City of Charlotte)

Driggs to head transportation committee: Charlotte Mayor Vi Lyles named Republican Ed Driggs as the chairman of the City Council’s transportation, planning and development committee. Council-watchers saw the appointment of Driggs, who has been skeptical of some of the city’s transit ambitions, as a sign that the proposed $13.5 billion transit plan would likely be scaled back.

Charlotte transportation summit: South Charlotte Partners is holding a regional transportation summit on Monday from 8:30 a.m. - 3 p.m. at the Ballantyne hotel called “Transportation in the 21st Century.” It will include a variety of speakers discussing transportation and mobility in the south Charlotte region and beyond. Details here.

Transit Time is a production of The Charlotte Ledger, WFAE and the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute. You can adjust your newsletter preferences on the ‘My Account’ page.

Did somebody forward you this newsletter and you need to sign up? You can do that here:

Other affiliated Charlotte newsletters and podcasts that might interest you:

The Charlotte Ledger Business Newsletter, Ways of Life newsletter (obituaries) and Fútbol Friday (Charlotte FC), available from The Charlotte Ledger.

The Inside Politics newsletter, available from WFAE.

The UNC Charlotte Urban Institute newsletter and the Future Charlotte podcast from the Urban Institute.